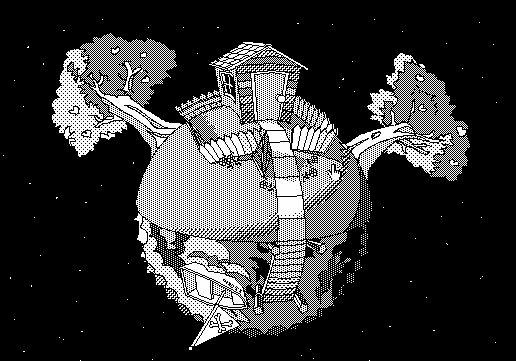

Cosmic Osmo was selected by the reading group I'm part of, as the representative of 1989 in gaming (we do things a year at a time). The person who identified Cosmic Osmo as the representative of 1989 framed it in this way: we may well be aware of SimCity, Prince of Persia, and the Game Boy, and if we are aware of these things we probably see them as the germs that would develop through the nineties and two-thousands and which we can still see flowering today. These bland teleological stories are what this particular reading group tries to redress by returning to the texts that confront us with the liveliness of history. 1989, Cosmic Osmo's sponsor tells us, was a year where home computers had proliferated and nobody knew what to do with them, GUIs had replaced text-based interfaces, accessible creativity software was growing in popularity, and the mouse was now essential for navigating this terrain. What struck me about Cosmic Osmo on playing it is the way that it seems to draw attention to the strangeness of the home computer we use to play it.

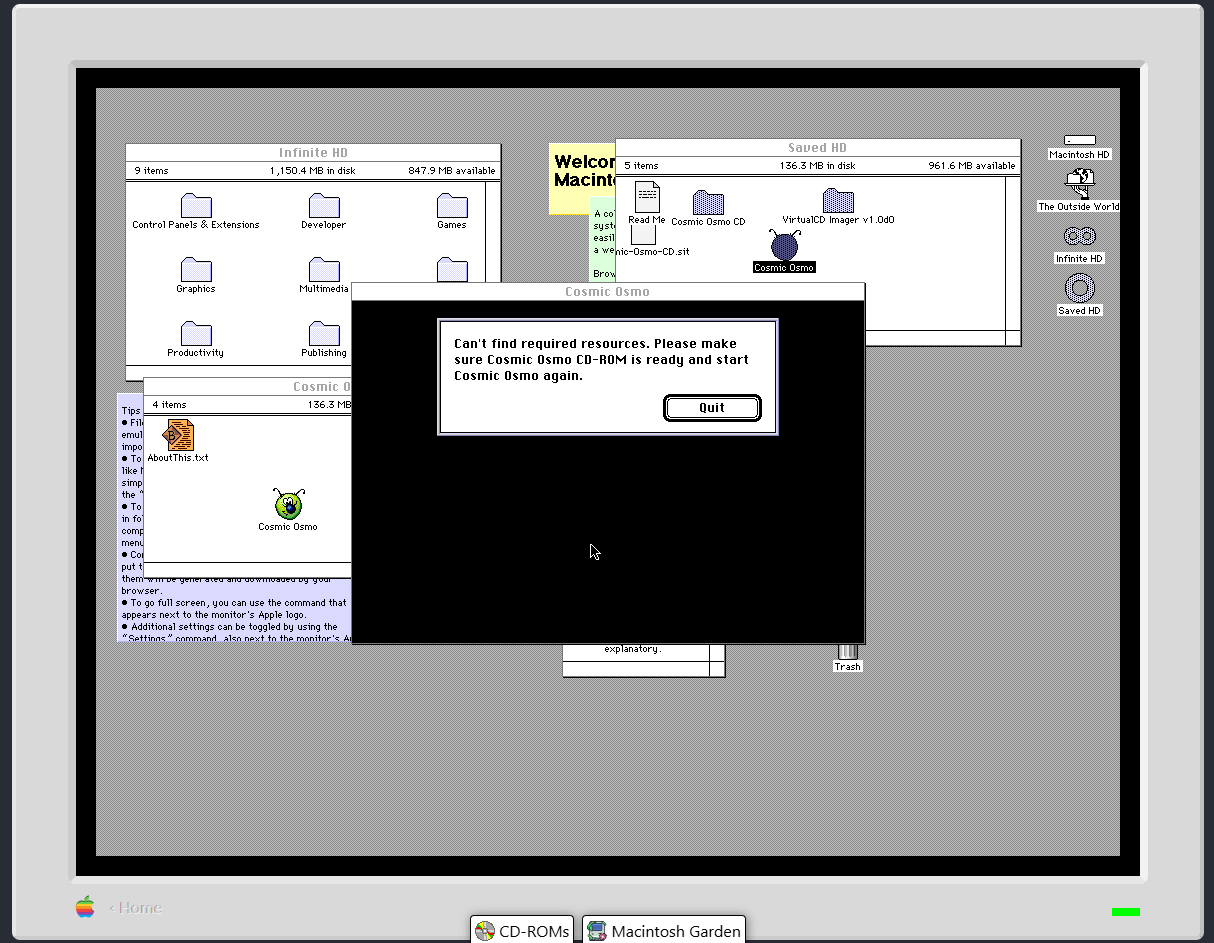

We played Cosmic Osmo through the Mac OS emulator site Infinite Mac, specifically System 7.5, which was released on September 12 1994. What Infinite Mac could accomplish in a few simple menus, it does through an emulation that puts us 'at' the console, dragging things about, appreciating the physical traversal of a desktop that has relatively recently come to require the use of the mouse.

Even installing Cosmic Osmo on this virtual machine is labour-intensive. Process, as well as software, has been archived. I'm reminded of how busy Macs have always felt to me. There's something primitive about Windows machines, and how clicking the 'x' button while in a programme abruptly closes it. Macs by contrast are all floating windows, programs that are latent and never not there. This exposes the sleepless logic of Random Access Memory in a way that's deeply uncanny to me. And I know this is part of its identity as the 'creative' machine. Creatives have things open everywhere because their workflow is rhizomatic and agile and frequently behind schedule, where annoying squares hold onto the illusion of discrete blocks of information, linear processing, closure.

I once quoted a friend Kittler's famous "There is no software" and he looked puzzled and said "There is no hardware either."

The joy of clicking things is really odd, because we're always clicking things now. The 1994 Apple emulation provides a hermeneutic frame by which we can stand back and re-experience what is now commonplace. I'm unsure if there's something immanent to the system that allows me to bracket this, or if it's just reactivated my personal memory of clicking things in the 1990s, where to click something meant to depart from where we currently are, with all the science-fictional optimism this entails. What I mean is, I remember very well the myth that the computer takes you 'elsewhere', and will occasionally find I've not wholly surmounted this, despite my best efforts.

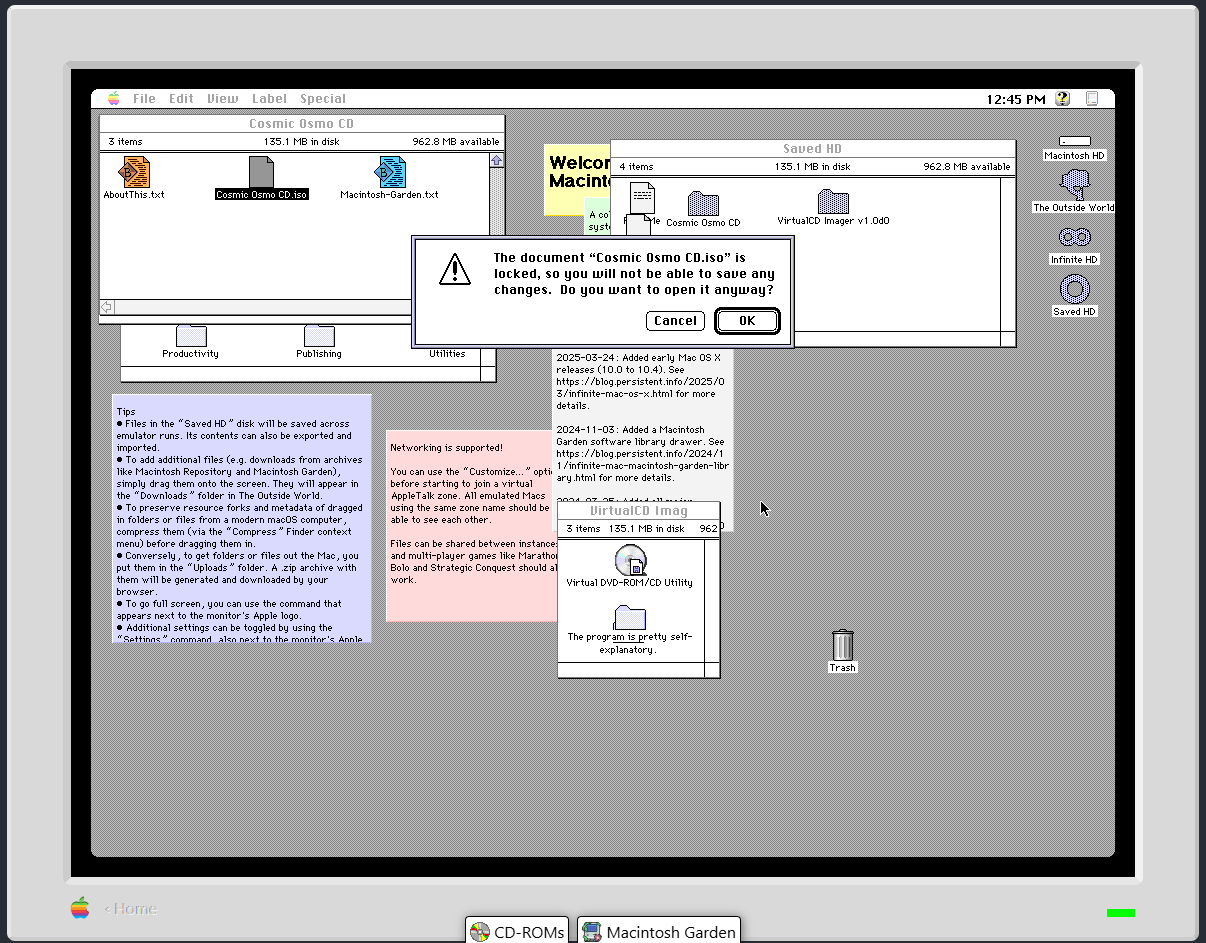

One of the first images we encounter is of a living room. It must be said these domestic illustrations are Kenneth Price by way of Gary Larson. People disparage Larson and approve of Price, and Robyn Miller sees through it.

It's important to remember that virtual environments such as these possess a latent animism, and that as well as 'departure', the click denotes the command for things to 'come alive'. Computers were at one point spaceships to the beyond, and proof that mechanism had overcome vitalism, that when Samuel Butler watched a potato sprout toward the light he had indeed discovered and demystified life all in one go. In the spirit of Butler, clicking the musical notation on the wall in Cosmic Osmo causes a cello to come alive and dance for us. Pajama Sam was full of things like that too. You'd click the rug and it would talk to you, telling you it enjoys eating dust.

Nothing is more unnerving than the home in graphic adventure games. Developers knew that if you were playing their game, you were sitting alone, in the dark, at home, bringing inanimate objects to life, and that there was something very lonely about that. Cosmic Osmo combines the exploratory and uncanny functions of the click by placing the home in outer space.

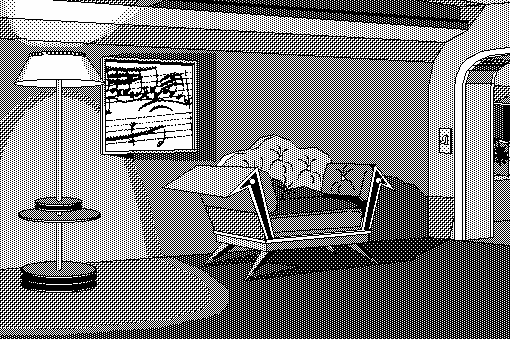

I've clicked the lamp, and it's dark.

"If we examine closely the lesson in philosophy the poet gives us, we shall find in this passage a spirit that has lost its "being-there" (etre-la), one that has so declined as to fall from the being of its shade and mingle with the rumors of being, in the form of meaningless noise, of a confused hum that cannot be located. It once was. But wasn't it merely the noise that it has become? Isn't its punishment the fact of having become the mere echo of the meaningless, useless noise it once was? Wasn't it formerly what it is now: a sonorous echo from the vaults of hell?" (Bachelard)

Clicking the lights makes the switch 'come alive', and the homeliness of the image 'depart'. It reveals "a sonorous echo from the vaults of hell" in the safety of the home. The 'being-there' of the home is made to depart through the use of the click. In a less domestic space this no-longer-being-there happens to look very nice.

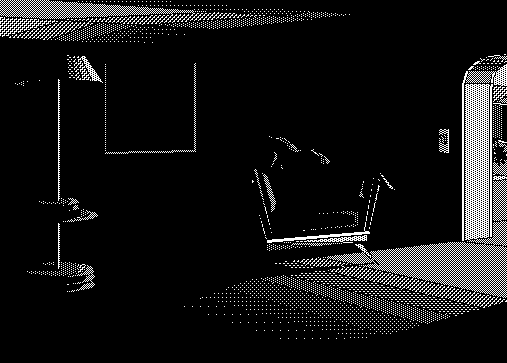

The cockpit has a CD player and CDs. There's something terribly isolating about the vocal CD once you've put it in. An echo bounces off it, very space age pop but digital and corroded. Whose voice is it? If Infinite Mac allows you to bracket the experience of using a computer, the cockpit in Cosmic Osmo allows you to bracket the experience of running antique software, alone, on the sad little computer in your house. Outside there's nothing, the darkness of night or coldness of outer space. In here there are things to click. And when we click them they perform for us. They cut through the silence, and it's awful. In cutting through silence they cut through time, because they don't know or care that it's been thirty six years and the world's forgotten them. They only know 'on' and 'off', 'click' or 'clicked'.

I called my old home's phone number, and the sounds of the keypad made me very sad. I decided to use the 'depart' function of the click and find a planet to explore instead.

This one distills… something. I'm not sure what, but it distills it. You might say 'what are you talking about -- everything distills something!', and you'd probably be right, but it's what I can't think that this distills that makes the distilling significant.

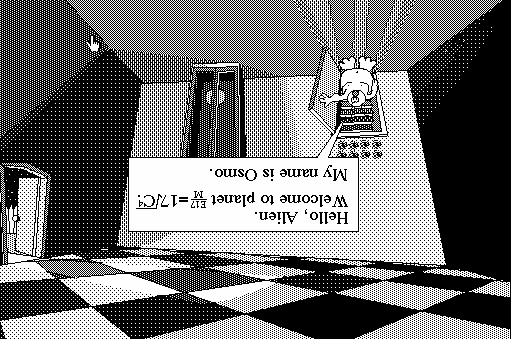

I disembark the horrible home and click on the one on this planet. It belongs to Osmo -- the individual whose voice appears on the vocal CD I listened to earlier. Osmo calls us 'Alien' and stands upside-down in the room. It's safe to assume then that we're the aliens, and we're the ones standing the wrong way up, which underscores the being-without-home of the Cosmic Osmo play experience thus far.

To turn the right way up is to forgo the home of the spaceship and attempt to integrate into this one, which is appealing because it has other entities in it that aren't possessed cellos. There's an intermediary step, though, and that's in changing size. We must be something like twenty feet tall at this point. This is interesting, because it develops the dialectic of the click from before: we're departing the before-state by integrating with the alien-home, via a logic that recalls a game from childhood, where the space of the home is made unfamiliar. In one of my favourite books Eleanor Kaufman writes about how games produce virtual worlds atop the actual:

I will examine the space of the lived-in house and the way in which the architecture of everyday life might be said simultaneously to give rise to new virtual worlds. To start with an example of how the virtual inheres in real-life time and space, one might picture what would happen if the space of the house were literally turned upside down. Perhaps it is the child's game mentioned earlier in which you turn your head upside down so that the house's ceiling becomes its floor, and you perceive the huge moldings that would have to be straddled to pass from one empty room into another. This is an exhilarating and spacious game, for there is no stuff cluttering the ceilings, just empty rooms bordered by foot-high fences; it is a minimalist and ethereal space uncluttered by the objects below. The upside-down ceiling world of the house is entirely composed of actually existing space, yet it is a space viewed from such a skewed angle as to seem altogether otherworldly. Furthermore, the ceiling world exists on a level that is in between. Assuming one is on the first floor, the ceiling world forms a sort of mezzanine between the first floor and the invisible second floor, which from this topsy-turvy vantage point becomes the ceiling world's basement

I wonder whether Kaufman ever played Cosmic Osmo?

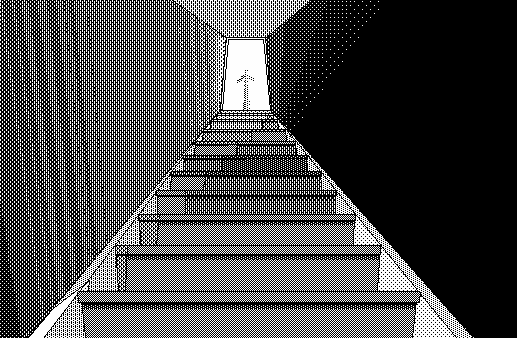

With one click we depart the state previously occupied and become the size of Osmo. He has a wall of what look like hamburgers but are actually eyes. When you click them they blink! He offers to take us to his leader, and for a moment you will think this is his leader:

In looking for the leader, I found this dog. He says if you feed him a bone he'll show you his belly, and when you feed him a bone he does! If your cursor is near his belly he'll laugh, and if you remove it he'll whine. The burden of virtual animism is the neediness of the computer program.

Clicking the arrow on the bottom-left takes us to a boat, the S.S. Osmo. There's a phone onboard. If you dial 555 7172 (the number on the ship), you get through to the computer, who says "Uh this is the computer on Osmo's ship and he's not here, so call back another time." Sentient spaceship computers have been a thing since probably before HAL 9000. In M. John Harrison's novel Light (2002), a woman has decided to unburden herself of subjectivity by transforming into a spaceship, and the problem is she's still burdened by sentience. I wonder what kind of entity the player-character is in this. We shrink and grow and go upside down until it's not clear whether we are or have ever been a 'stable' configuration of size and gravitational compliance. It'd be easy to say we're disembodied, and more accurate to say we're embodied everywhere. I think this better achieves the dizzying perspectival scalability than Harrison's novel, which frequently resorts to the image of velocity as a shortcut to bewilderment. The otherworldly stillness of this game reminds us of what we knew as children and tried to forget, which is that there is no 'stable', that walls have eyes, that the top floor of a building is concurrently its deepest, darkest basement.

Shortly after phoning home I sailed to an island with a coconut tree, a boulder, and a sundial. Clicking the boulder reveals a keyhole, and clicking the coconut tree causes a coconut to fall, breaking, and revealing a key. Dragging the key to the keyhole fires a beam at the sundial, and clicking the sundial after this removes the lid, revealing a liquid. Clicking the liquid after this causes a very small submarine to emerge. Clicking the submarine allows us to go into it, where we meet a mouse. The hallucinatory play of scale here becomes hard to follow here, because every click has us depart again, and it seems as though we're folding in on ourselves, and folding again, until at some point we have journeyed so far inward that we discover the skyscraper we flew past a few hours ago, back when we were a ship.

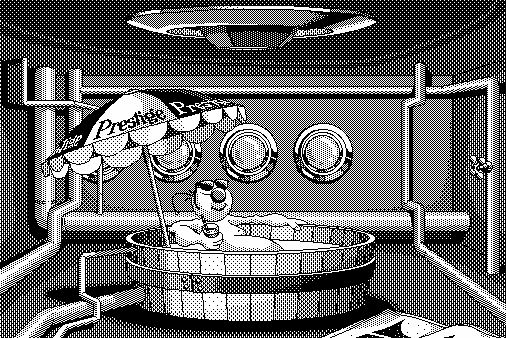

The mouse takes us on an underwater journey, popping up at 'Tub'. 'Tub' is a hot tub!

Clicking into the next room, and then into the circular ceiling, reveals that we've been under a microscope, the size of an amoeba, this whole time! And so now we are the size of the microscope that has been watching all of our actions on the amoeba level.

The elevator in the background connects us to seven possible floors. I've not met the leader and I've gone from alien to mouse to amoeba size, and the amoeba was always bigger than the mouse, and one of these doors leads to the surface (?) of the planet and on the surface of the planet we become ship-sized. In a way the ship is always amoeba-sized, just as the amoeba is planet-sized.

The microscope is an image that follows me through my playthrough. Susan Stewart writes on the melancholy of miniatures, that "The most miniature objects cannot be 'seen with the naked eye.' The body must be clothed in an apparatus, a technological device. The miniature, or microcomputer, is the absolute culmination of the gadget; the transformation of the tool, with its human trace, into a mechanical extension into space" (102). I'm not sure that's the case in Cosmic Osmo? Or, at least, by using the computer we become cloaked in the apparatus that allows us to access the miniature as well as the gigantic. I wonder if there's something in that -- the adult is drawn to the miniature because of its arrested time, and the pathos of the details they can't access. The child by contrast sees the miniature as gigantic, and Cosmic Osmo moves according to the logic of this infinite folding, this proliferation of the virtual through play.

I'm dizzy. I think I've been pretending the ceiling is the floor, and that the floor beneath me is the sky, for too long. What am I trying to say? Nothing, but Cosmic Osmo is a very moving experience. The game comes from a time where the computer was sold as a thing that grants us access to an 'out there'. As a text it deliberately gives shape to the idea that if the home can become otherworldly through the play of imagination, one of the virtualities latent within it is loneliness, and the computer is the machine that produces this.

In her paper ALT + HOME: Digital Homecomings, Rachel Wagner effuses about digital homes (whether the homepage of a website or the desktop of a computer), writing "Increasingly, home has become less a physical site of inhabitation than a marker of movement, a trail of pixels, a trace of where we have been and a longing to find the beginning of things--an impossible but oddly powerful compulsion" (87). The compulsion to find the 'beginning' here is interesting because it inverts the long-held structure of homecoming that started with Homer's nostos, in which "a voyage out is only incidentally a journey of discovery and victory. Primarily it is an ardent quest to return home" (Reed 2006). The compulsion to find the 'beginning' was for almost three thousand years a compulsion to return to the beginning, in a text that begins with our estrangement from home and progresses through the desire to close this gap. But so now the computer home is present at the beginning. The home is always a portal, or, rather, a port. We know the home only by our departure from it.

The click then is the mechanism by which we depart, fulfilling the dualist fantasy of the computer as a ship to another world or set of worlds. And the other function of the click, as I've said, reverses this. It commands what's before us to perform. If in the first function we disappear from the here-and-now, in the second the here-and-now comes vividly alive. In one the machine issues a departure from the home, in the other the machine makes the immediate environment obtrude in its strangeness. It's uncanny because two beliefs, surmounted since childhood (techno-dualism, techno-animism), come rushing back in convincing form. Cosmic Osmo captures this dual loneliness and liveliness better than any text I've encountered in recent memory.

Back at my childhood home, the computer sat in 'the office', a small cold standalone building up a shell path from the main house. There was another standalone building further up, 'the shed', where my dad would work on motorbikes. He had inherited a Triumph from his late father and would spend evenings staring at it and chain smoking and cursing British engineering, and then he'd work on his Bimota and chain smoke and smile and praise Italian engineering for the grace and elegance of its flaws, which he found reckless and exciting. There was always something shameful about having to leave the house and go out into the office to use the computer, and returning a few hours later you'd swear the house was now kind of 'off' and 'against you', but really it was just the shame.

I wonder about the 'longing to find the beginning of things', and the compulsion to homecoming that Wagner writes about, and how the virtual home as a point of departure features in the emulation of antique operating systems. That is, even without considering how the older text might function as a homely destination, programs like Infinite Mac archive the infrastructure of the port itself -- the thing from which, conventionally understood, we only ever depart. Now we try to reverse the inversion of Homer, embarking from our computers to the homes we left long ago, only to find there's no software and no hardware either, and that in so easily finding the home we also find that we have lost the object of homecoming so to speak.

30 July 2025