Seabird's Maggot Mix arrives at Slipknot's twenty-fifth anniversary, during a surge of interest in nu metal from younger listeners. This is good news for listeners young and old --- it has never sounded so vital. To my ears it amplifies the sense within the original record of something that's actively addressing me. Much of this renewed vitality comes about through Seabird foregrounding the original album's sonic clutter. Corey Taylor screams and cowers into a microphone so sensitive it registers the voice as white noise. Half-digested samples, putrid or otherwise coated in dust, intrude on the live event of the voice, not so much coming to life as dragging the voice screaming to its own undeath. Images of digestion, putrefaction, and the undead are apt because Slipknot is an album fixated on the abject. It's cloaked in sickness, and it makes a spectacle of the way it almost falls apart. It's always almost falling apart, and then finds itself unable to go through with it. It lashes out in cold sweats against the pull of inertia, against the already-known, against the perfectibility of art and life. Unable to die, it's a record that's always starting again, battered and different.

***

I've been talking to Seabird about music for a decade now. For years it was all The Fall and Joy Division bootlegs, and never anything like Slipknot. Out of nowhere it happens:

seabird --- 7/06/2023 11:26 am

im listening to slipknot as we speak

I don't know what to do with this announcement. I don't like Slipknot in June 2023 and I had never liked Slipknot before June 2023 either. It was twice expected that I like Slipknot: I was nine years old when the Spit It Out single was on the radio, and fourteen when Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) came out. All of my friends were excited by the impenetrable chaos of the debut, and the melodicism of the later album. In 1999 I was confused by the fact that a band who were being compared to KoRn would sound so macho. In 2004 I was confused by the fact the man in the scary mask was now singing like a particularly benign Trent Reznor doing both big rock choruses and tender campfire songs.

Seabird continues talking to me about Slipknot through June. It appears he's listening to different mixes and issues, and cross-referencing them with live recordings and studio outtakes. I'm not sure this will go away any time soon. It takes five days for me to respond:

maxcoombes --- 12/06/2023 11:18 am

slipknot is NOT friendly!

***

Renewed insistence on Slipknot's liveness is critical. I say this because it's the listener's job to listen, and to listen is to ensure the meaning of the thing is never exhausted. Maggot Mix does the unsettled work of the listener and puts it to sound. It's comprehensive. It's read and read and scoured material and like anything done for love it actively works against the idea of closure, underscoring instead the idea there will never be a 'final' version of the object of its obsession. As a creative reworking it reveals the seams in the 1999 album we either grew used to, or convinced ourselves were never there. This is important because the original record is so clearly a collage. It could never have even pretended to be a stable artefact, it's so brittle, mercurial. Everything in it sounds reconstituted, rotted, sewn together with frayed edges gaping. The vocal is dry but the mic rattles in mucous, transducing the appearance of blood in the throat. Sometimes it sounds like the sticky, raw flesh beneath burns or frostbite. Other times it's so void of human timbre that it's more the sensation of cold wind or blinding heat. Drums burst under tin can percussion and breaks clearly sampled give the impression of 'breakbeat' and 'jungle' and 'techno'. Guitars are the memory of some ancestral metal group, coming in and out of prominence. No sound appears entirely necessary, and consequently everything present is equally important. There is a desperation to the thing that obtrudes most when it appears to disintegrate. This desperation propels things forward, and every sound fires off in its own direction, returning to us a moment of urgency elsewhere.

***

For all of its merits Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) sounds sunburned and horrible. It sounds like a hard rock album from 2004. The former complaints might come down to an unfair association. Slipknot played at the Big Day Out festival here in January 2005. The friends I went with were excited to see Slipknot and System of a Down, two bands I didn't like, and gave me shit for more or less going just to see Le Tigre. Early in the day I went to use one of the portaloos and decided I'd not eat food or drink water for the rest of the day so as to avoid having to go back. I lasted until midday in the summer heat before passing out in the stands from heat stroke and dehydration. I don't remember how I got home --- the last thing I remember seeing was nine men in jumpsuits and masks on a stage down in the far distance, the sound they produced folded at such a dramatic right angle that I could not decipher any of it, could not say that I disliked it, could only say that it was Slipknot.

***

Maggot Mix's sonic collage invites, or rather demands, we interact with it. The idea of such a live-seeming collage might sound strange. One of the more prevalent myths in music is that the albums recorded live, with as few overdubs as possible, are the ones that are inherently 'immediate'. But in the Slipknot collage, everything is sample, is overdub, is buried and brought back, and seems to stare directly at us. In trying to figure out how and why this is, I'm reminded of Michael Fried's categories of 'theatricality', 'absorption', and 'facingness' in painting. According to Fried, 'absorptive' painting shows figures absorbed in some task within the world of the painting --- like a one-way ethnographic mirror, the viewer can gaze upon the 'live' event, totally unchallenged. 'Facingness' in turn adheres to absorptive techniques while reviving the 'theatrical' tradition of painted figures looking back at the living viewer. Facingness is not only a matter of figures returning the gaze, but forcing the viewer to make sense of an incoherent picture plane. Fried observes there's an immediacy to the dislocation of surfaces, and that the live address of figures present accompanies the viewer's awareness of the painted surface as a painted surface. Bare artifice dissolves the frame and crosses over into the real. In one sense the work comes alive through the involvement of our bodies. In another, our bodies are ensnared in disordered unreality.

I think about this as I'm listening to the Maggot Mix. Perhaps we value the ethnographic 'absorption' of records too much --- the lie that we are watching something play out, something not deliberately arranged for us and engineered to please our ears. Slipknot both addresses us, makes demands of us, and puts up sonic barriers to thwart the easy transfer of our concern. Its dislocated surfaces need to be imaginatively pieced together as the record plays, where the ethnographic record arranges its noises for us as sound. I can hear the pained, physical activity of the musicians playing, and I am never not aware that they're lost somewhere in the confusion of the mix. The injured sound of some of the recordings points to the fact that all of this is damage, all recorded, all swarming as a matter of machinery, the musicians all gone. I can receive its sounds as sounds, abstracted from the human performers, but still they betray a live reality that a more 'live' recording keeps safe within the confines of the album. In the absence of any such frame I become aware that there is no way to engage this record without it looking back at me. In this we become intimate with its noise; active participants in the construction of Slipknot. Owing to our activity, its sounds become active too, alive in our heads and in our bodies. When Taylor intones "You can't kill me 'cause I'm already inside you," we know for better or worse this to be true.

What continues to make Slipknot so startling a listen is that it is itself startled --- horrified by what it sees, and what it knows it is. A great deal of its restlessness is its struggle to delineate these two things. With no course to separate itself from the world, it embarks on a journey both spiritual and ethical. It's a search for the purity of the voice, in a world of disease and clutter.

***

On the first of September 2023, three months after telling Seabird that Slipknot is not friendly, I rewatch Saw (2004) with friends. The minute Billy the Puppet appears in the film, riding his red tricycle, Gabriella yells out in recognition "Slipknot!" We all laugh at the idea of Slipknot being a single person, dressed as a puppet called Slipknot. It's only much later I realise she was referring to the Spit It Out video, in which drummer Joey Jordison rides around on a trike in homage to The Shining. In hindsight Slipknot's 1999 debut has a lot in common with the 2004 films Saw and House of 1000 Corpses. All three things Frankenstein a naturalistic presentation of subject matter with noisy, resampled, experimental footage of the same; all embrace an agitated, carnivalesque theatricality; all are convinced that human bodies come already green and purple bruised, weeping oily blood from very, very old wounds.

***

Let us begin with the assertion that there is no voice that speaks purely from the soul. The promise of sound as an abstract medium initiates in us a search for the sacred in what is always infuriatingly profane, physical. The dirt of sound precedes and survives the advent of recording equipment: acoustical engineering concerns how buildings and open spaces all exhibit their own code for the physical presentation of the voice, rather than disclosing how the voice 'is'. This is because the voice never 'is' outside of its collaboration with the environment that delivers it. Sound is profane; a physical vibration. Sound recording then embalms the voice and its environment in a new physical container for future storage and delivery. Playing the recorded voice brings that environment into this one, but it also marks a temporal severance between speaker and recipient. Every instantiation of the recorded voice attests to an impassable distance, the speaker long gone. I think of this listening to Slipknot, because it attempts to close this distance by addressing itself to 'you', that's 'me', that's 'us'. Taylor might have lost his voice to the recording, but the recording sees us, addresses us, speaks to us, as though it was and is still live.

***

Much of the anxiety that runs through Slipknot appears to stem from the monistic view it can't shake: mind/body, self/other, body/world are all proven to be of the same stuff

Bodies are distinguished from each other in respect of motion and rest, of swiftness and slowness, but not in respect of substance

---Baruch Spinoza, Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order

One issue is that this single substance is, notably, diseased

Clearly, these are not primarily anxieties of loss in the sense of the Freudian account of castration anxiety; they are rather anxieties of excess, of flowing over, of unstable bodily boundaries. Significantly, these anxieties are often followed by a sensation of a total dissolution of boundaries, a merging of inside and outside that is also experienced by Malte as threatening and invasive (...) Rilke's constant use of the imagery of disease and filth, aggression and death clearly points in a different direction. Indeed, we face the paradox that these visions of bodily excess are simultaneously experiences of loss.

---Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia

Another is that Taylor is worried he doesn't know himself as himself, only as a thing in the world, affected by other things in the world

The human mind does not know the human body itself, and it only knows that it exists through the ideas of the affections by which the body is affected

---Baruch Spinoza, Ethics

It's in Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) that Taylor decides to meet his critics, and write lyrics that continue to probe his fixations but without profanity and gore. What this means is you get a very simplified version of the anxieties that run through Slipknot and Iowa:

I am all, but what am I?

Another number that isn't equal to any of you

I control, but I comply

Pick me apart, then pick up the pieces

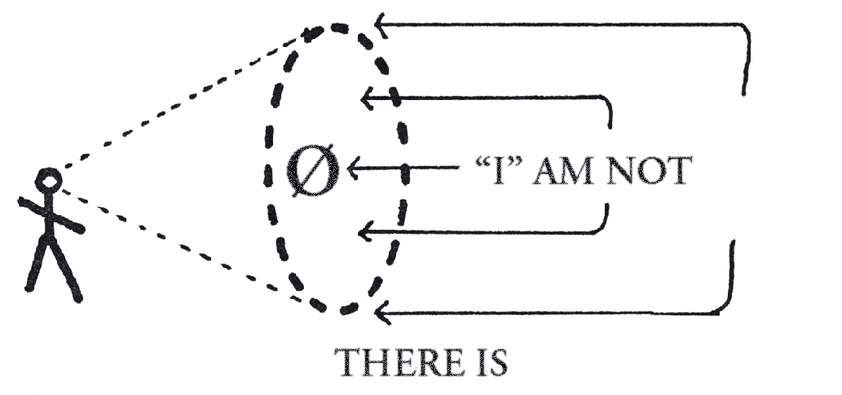

If we're all of the same substance, how can one individuate the 'I'? If we're always in the process of being affected by things external to the 'I', where can we locate free will? To be affected is to be capable of affecting. True to the band's monistic view, this is not just a lyrical preoccupation, but something that animates the album as a whole. I wonder whether this is the realisation that Slipknot seeks to elicit in its constant address to the listener: you can't observe something without yourself being observed.

***

It is astonishing how many belief systems hold the body to the standard of purity. The body's inability to become pure leads to not only a hatred of the body that cannot be cleansed, but the fashioning of barriers between the would-be pure body and the contaminating influence of the other. Slipknot was released amidst violent assertions of national, ethnic, racial purity, in the half-light of the century of atrocity. Rather than embarking on a totalising political project to combat this, Slipknot investigate the myth of purity at a more foundational level. They ask how best to live knowing that 'I' am never as stable as 'I' would like to be, that a culture is defined by who and what it rules out, that the existence of the other both affects me and evades my comprehension. Their approach is intimacy with the abject, knowing purity is an impossible idea: whether it's the chemical makeup of the air, the bacteria, fungi, and viruses that constitute the human body, it is always infected by the world it ingests and through which it is born and kept alive. It collaborates with its environment for expression, and its environment expresses itself through the body in turn. It is always already inside-out with its environment. Slipknot make a point of staging this realisation in every song, with Taylor's character trying to keep the outside out, and the outside intruding in the clutter of the music, with its enveloping death and disease.

***

Because every 'thing' affects every 'thing', being of the same substance, then even a glance induces a violent irruption of that 'thing', undoing that 'thing' and proving it both permeable and permeating. There is no negative space. Corey Taylor addresses us as 'nothing', as a corpse, as, most frequently, a disease.

What is noteworthy about the pre-modern concept of plague and pestilence is not only its blurring of biology and technology, but the profound lability that the concepts of plague and pestilence have. In the chronicles of the Black Death, plague seems to be at once a separate, quasi-vitalized 'thing' and yet something that spreads in the air, in a person's breath, on their clothes and belongings, even in the glances between people

---Eugene Thacker, "Nine Disputations on Theology and Horror"

The corpse (or cadaver: cadere, to fall), that which has irremediably come a cropper, is cesspool, and death; it upsets even more violently the one who confronts it as fragile and fallacious chance. A wound with blood and pus, or the sickly, acrid smell of sweat, of decay, does not signify death. In the presence of signified death---a flat encephalograph, for instance---I would understand, react, or accept. No, as in true theater, without makeup or masks, refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live

---Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection

***

It might appear strange for a band dressed in scary costumes to explore the question of how to live authentically. What the group do with Slipknot is a radical dressing-down of the self, enabled by the anonymity of the costume. They make the point of starting from zero when Taylor barks "I am my father's son / 'Cause he's a phantom, a mystery, and that leaves me nothing". How does a nothing come to define itself? Taylor's first attempt is to craft a psychical reality to inhabit, sealed off from the outside world. This nothing becomes something through its fantasy-partitions: "Inside my shell, I wait and bleed" (Wait and Bleed), "Tearing myself apart / From the things that make me hurt" (Tattered & Torn), "I haven't got time for the living" (Diluted), "You all stare, but you'll never see / There's something inside me" (Purity). The guiding principle here is that the madness of the self is authentic because it betrays an imperviousness to the reality principle --- the outside cannot read me, and I cannot read the outside. Here the abject sonic landscape of Slipknot is abjected by the vocalist --- cast out so that he can maintain a stable self. As Julia Kristeva writes,"The abject has only one quality of the object---that of being opposed to I" --- so Taylor's panicked, defensive protagonist holds everything beyond the self to be its potential undoing.

***

Assuming Seabird's Slipknot project had something to do with a curiosity about the year 1999, I asked if he would next be looking at The Slim Shady LP, that other paragon of multi-platinum selling grotesque realism released at the turn of the millennium. He said he probably would, but that it would have nothing to do with Slipknot or the year 1999 specifically. Listening through the mixes I soon realised the closest point of reference for Slipknot's mood isn't the cartoon hell of The Slim Shady LP --- it's Eyehategod's Dopesick, the lethargic Southern Gothic masterpiece whose only relief from the thick blanket of blood and vomit is the cold sweat that keeps its body writhing. I still don't know what to do with the comparison, so maybe that's something.

***

It doesn't work. What the retreat into fantasy forgets is that, in abjection, the self can only define itself by what it excludes. Intimacy with the abject is needed to "show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live." The messiness of this process is such that "I expel myself, I spit myself out, I abject myself within the same motion through which 'I' claim to establish myself (...) I give birth to myself amid the violence of sobs, of vomit." Taylor's body is germaphobic, paranoid, deathly afraid of impregnation by the outer. However he tries to control things though, the noise and smells of the physical world intrude, reminding him of his own vulgar, bodily externality. Being embodied, every confrontation with the world affects him, lives inside him, alters him. We see his horror at this expressed in the motif of permeable skin --- "It's hard to stay between the lines of skin" (Scissors), "I can't see, I can't be / Over and over and under my skin" (Surfacing) --- and in the permeability of the self and other - "I see you in me" (Diluted), "Someone behind me, someone inside me" (Scissors), "Tearing me inside" (Inside). The nothing that Taylor wants to be is not a stable zero, but a relational thing, coming into and dissolving its being with every painful interaction. The interactions Taylor demands from the listener spurn passivity --- as I've said, Slipknot is an incessant communicator, making demands of 'us', telling 'us' what 'we' have done, interpellating us as things that it can see and feel and affect.

***

The song Purity is based on and uses samples from an online 'true crime' story that proved to be fictional. Its fictionhood known, it was determined to have been produced in violation of the author's copyright, and was pulled from the original release. The congenital impurity of Purity haunts Slipknot --- it's at least as interesting as Scissors, and in terms of performance might be the album's most affecting cut.

"I still think it's real. See the thing whether it's true or not, it's a real story, that we read about, that fucked our whole world up"

---Corey Taylor

At risk of valourising untruth, there's something interesting about the unreality principle demonstrated here. Unreality can "fuck your whole world up," and is therefore "real," whether or not it's "true." Slipknot dress and produce music as (fictional versions of) horror movie entities (fictional killers). Important here is that this strategy makes for a relational nightmare. Taylor cannot seal himself off in fantasy, but he can share it, like a virus. It's untrue, but it comes into reality whenever you hear and remember it. You are its host organism.

***

How then does Slipknot shift from a series of things happening to its embedded protagonist, to a work that communicates outward, to the listener? In Scissors it's decided that a ritual autopsy is needed: "Before I cut my heart open and let the air out"; "As I lie there with my tongue spread wide open." The intention behind the ritual is to reverse the shuddering fear of the outside, by opening up and polluting the world with the organs of the self. It's through ritual that the opening sample "The whole thing I think is sick" is made to connect with the album's first mantra-proper "You can't kill me 'cause I'm already inside you." Following the ritual Taylor is no longer an 'I' nor a nothing: he is sound, is disease, is parasite. As parasite it lives in the body of the listener addressed in 1999 and which it continues to address two and a half decades on. Received wisdom dictates that the voice becomes more than the body that sent it, its disembodiment a form of transcendence. In Slipknot it's emphatically less. Descending rather than rising, neither subject nor object, the voice here is only expulsion, contaminant, the dust of undeath, fucking up your whole world.

***

So this is the gradual unfurling of Slipknot's monism into the body of the listener. Nothing comes directly from inside for the simple reason that there is no inside.

Trieb gives you a kick in the arse, my friends --- quite different from so-called instinct.

---Jacques Lacan, "Seminar XI: The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis"

I am the push that makes you move

---Slipknot, "Surfacing"

***

Rasping through my ears is the voice of howling wind. Perhaps the microphone in Slipknot is very sensitive and Corey Taylor has sung into it so quietly that it has only detected the expulsion of air. Or perhaps he has sung so loudly that he has overloaded the signal, transducing the voice into a flat blanket of distortion. In either case it has eliminated human timbre, sounding like the wind. Taylor on Iowa will adhere to recognisable heavy metal vocal techniques, and on Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) he will deploy a lovely warm baritone. Both records want you to know there is somebody using their diaphragm to throw the sonorous voice you hear and enjoy, like thumbprints left in clay. But that is the future. The voice in Slipknot was at some point one with the sensitive microphone, and since then it's become one with the distorted surface of the recording. I emphasise 'surface' here, because the scream eliminates depth. It chews up and shows you the tape. If the voice and its mediation are inextricable, then what the scream does is tie the two together in violence. The event of the scream damages the recording surface, and the act of recording the scream damages the body of the vocalist. Playing the recording enacts this originary violence in real time, damaging the ear as well as the active, moving bits that constitute the audio system.

The nonhuman timbre of the voice Slipknot advances two, ostensibly contradictory ideas. First, the excesses of the voice have it outstrip the limits of the body, becoming something pure, and elemental. Second, the overloaded signal dramatises the impossibility of accessing the voice beyond the material recording. One of these ideas is transcendent, the other a matter of descent. They are both united, however, in their annihilation of meaning. To begin with, we are trained to hear the voice as though it is a meaningful expression of the body from which it emerges. In the transcendental ideal, the Sacred Liturgy makes present the Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ, fills the singers with the Spirit, and in so doing sanctifies the profane body. The condition is that the music must be beautiful and logical --- logike latreia, upholding the symbolic order of the hymn. In the secular humanist ideal, the voice escapes the word and becomes the carrier of subjectivity and soul. And so in Slipknot, the logical order of the word collapses, the subjective character and human physiology of the vocalist is obscured by the costume, and the voice itself is flattened into its mediation in white noise. There is no body, no spirit, no vocal-semantic content as such. The transduction here serves to remove the self from the real and re-present it as a crude material artefact. Not because this leads to a strengthened sense of 'I', but because it works as a kind of ego-suicide. And yet, the album wants you to know, through all of this, there is life.

I hope that I've conveyed some of the ways Maggot Mix rebukes the idea of an artwork's closure, and how this attends to the original album's fixation on undeath. At times the album boasts that it now lives inside the body of the listener; at others it bemoans the fact that it's now unable to die for the same reason. It would feel particularly disingenuous given the topic to suggest the listener's work is ever complete, so let me conclude by saying I'll finish writing about it now, until the next time I write about it. For this non-conclusion I'll settle on the non-closure, the unsettledness, of all media.

If the confusion of grammatical tense throughout this essay has been a headache, it's because every artwork expresses temporal confusion, and Slipknot absolutely insists on it. 1999 speaks through 2024's Maggot Mix in present tense, as though twenty-five years has not passed. By scraping from demos and live recordings, Maggot Mix grants presence to that which is outside of 1999, alongside 1999. In its collaged sound Slipknot presents its 'live' elements as though they are a past being resuscitated in samples. All of these knotted times are re-actualised whenever we experience them as music, carving themselves oblivious into the wounds not healed from the last time we encountered them. We remember them, but they don't remember us. We grow older and they do not. All they know is to come into being when summoned, and the best we can hope for as listeners is they never grow dull enough to allow us the time to heal. For that to happen the meaning of the artwork would have to have been exhausted. We would have failed to fulfil our duty as listeners. Fault would lie with us because of the artwork's radical indifference to the passage of time. It does not understand time, and is therefore never less vital than the day it was produced.

***

I tend to look for the historical picture when the text itself fails to resolve itself for me. I'm aware this threatens to turn the text into a symptom of a time I've only a vague idea about. By this method both the text and the time then cease to mean anything. You can say anything when nothing means anything. You can say that 1999 was very dark, and that is why Slipknot is so dark. You can also say that 1999 was very bright, and that is why Slipknot has clowns in it. And that in 1999 history had ended, and that is why Slipknot does not believe in real death. And that by 1999 history had never weighed so heavily on the world, and that is why Slipknot takes death so seriously. The possibilities are endless. It's too easy, which is why I try to begin with the text in all its confusion. In all its presence. I often fail to do this, and I'm sorry. It's much more work.

***

Media archaeologist Wolfgang Ernst argues that no media follow the unidirectional, progressive model of time we as humans use. For Ernst the activation of any media object constitutes an 'experimental event' that is endlessly repeatable as a performance between user and instrument. A book is an event when read, a painting when displayed, an album when played through stereo or phone or computer. Whatever the instrument, the media object is never static but is always latent, is not an artefact but always an imminent process ready to be activated. To bring it back to our example, Maggot Mix is not the arbitrary code underlying the multimedia representation, but is its actualisation, its motion, its noise in our ears. For Ernst this means that every experimental event creates a wormhole: "There is no 'historical' difference in the functioning of the apparatus now compared to then," he writes, meaning "there is a media-archaeological short circuit between otherwise historically clearly separated times." The object itself is only ever in a present and not historical state: "Seemingly historical media objects are purely of the present time as soon as they function." Ernst insists his thought is fixed to the perspective of objects, and not the human user, because "the cultural lifespan of a medium is not the same as its operational lifespan." Humans forget, but media do not, or, rather, media do not register that they've been forgotten.

***

I began with the desire to speak with the dead.

---Stephen Greenblatt, Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England

***

Something I love about Ernst is that he never manages to be wholly persuasive about the strategy where the human user is left behind. Sure, the media object adheres to the microtemporal logic of the instant, while the human user clings to the macrotemporal framing of time as history. But then Ernst admits that appreciating this is bound to fuck up your whole perception of time and matter. The disoriented subject is never far from the experimental event, and the media archaeologist simply pursues the disorientation that lurks within our every engagement with media. The insistent sobriety of his method makes him an ideal character in a Gothic fiction, always about to be undone by what he's found in the archives, but he never lets that happen, at least in his books. Tethering his perspective to that of the indifferent media object, Ernst is never allowed to ask why a text comes or goes from public consciousness, or, rather chooses to make itself known. Stephen Greeblatt discusses "textual traces" within works, which have them endure through history through the alignment of social energies and artistic process. For someone like Aby Warburg on the other hand, the trace or energeia is immanent to the text itself --- the text persists because it decides to do so, through the use of its own 'stored energy' (Energie-Konserve). For Warburg, textual undeath comes about through its obliviousness to life, and the undead agency whereby it's always driving itself into being. Following this Aleida Assmann calls every event of textual engagement a form of "speaking with the dead." I hope the strangeness of this isn't lost: she isn't saying the text is dead --- how could it be? The text continues to speak back to us! --- but that the ones who write and receive it are, for we either are already, or before long will be.

There's not much conciliatory about speaking with the dead. It's a matter of attending to unsilent fragments, of searching for and allowing ourselves to become disturbed by the occult surplus latent within any object. Because of this it's not a particularly popular activity. Assmann disparages experts who discuss texts as though they offer a fixed and accessible view of the past. She worries the text dies the moment its work is considered 'complete', and that the reality of the past dies with it. It's said the past is only really itself when it flashes before us with a sense of danger. Perhaps selfishly I'm more worried about the reader in all of this. What happens when we abdicate critical thought, or curiosity, or the imagination to welcome uncertainty? Is there any method that can counteract the deadening of art? Does speaking with the undead require an undead method?

Assmann argues the antiquarian tradition has proved that "Different routes of access to the past were opened by bypassing texts and tradition and concentrating on nontextual traces such as ruins and relics, fragments and sherds, and songs and tales of a neglected oral tradition." A warning here is that such a method is designed to fuck you up. It is the realm of the M. R. Jamesian hero, plunged into the insanity of the object that calls out to them, that speaks to them, that forgets them before they can forget it. This in turn is the realm of the reader, who must remain unwilling to let the text settle. How then do we open ourselves to such a grandiose undoing? I'm not qualified to prescribe anything. But the Maggot Mix is a good start.

15 December 2025