Perhaps it was naive to think the first chapter of Mother 3 would conclude with the deferral of the central family's reunion, and not with the tragic death of the mother I had, minutes earlier, named Garland. But so Garland is dead, the possibility of reunion has vanished, and the first chapter is not yet over. We're still somewhere in the middle of something that hasn't truly begun, and there is already the sense the game is wondering how it can continue in the wake of its lost mother. It's intriguing that the wake of an event arrives as an introduction, that a game named Mother is knocked off balance by the death of the mother the player never got to know, that we can only know Mother through the loss of Garland and the subsequent groundlessness of the text.

Although it's bewildering here, the drama of the lost mother isn't incongruous within the fantasy genre. I tend to think fantasy begins from the sense we've lost something, and harnesses the desire to recover that thing. Julia Kristeva insists this imaginary lost thing resides in the realm of the archaic mother, which is the state of undifferentiated being that prefigures the emergence of human identity. For Kristeva, fantasy is all about the desire to heal the originary wound that makes life possible. It could be that the death of Garland is something like a departure from the archaic mother: by all appearances the world of Mother 3 before we start playing it is a thing of perfect wholeness, not that we can access it. The condition of our entry into the text is the loss of the thing we never really had.

This idea seems to follow the writing of fantasy as well. C.S. Lewis describes the loss of his mother as like the sinking of Atlantis:

With my mother's death all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared from my life. There was to be much fun, many pleasures, many stabs of Joy; but no more of the old security. It was sea and islands now; the great continent had sunk like Atlantis.

---C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (1955)

And the same year explained to his readers that the way into Narnia is through the rings found within a box that survived from Atlantis. Atlantis and the lost mother haunt Lewis' fiction, which Bill Gray in Death and Fantasy (2008) points out survive his attempt to give things a clean resolution in the discovery of the afterlife. For his part Lewis is open about the fact the fantasy he writes exists to stoke the desire for a lost something in the reader, and that it endures in them on the condition that it is never found. The lost mother in Mother 3 echoes the lost mother in Lewis, and the loss of Tazmily Village echoes Lewis' Atlantis. It's a loss that not only permeates but structures the whole world. The death of Garland precipitates the corruption and dissipation of the idyllic setting we, once again, never got to know. The fact we arrive in the wake of things is telling: pastoral nostalgia, the Edenic garden of the past, is always already perceived from the side of its loss. Of course it was never real to begin with. It's a construction used to fill the void we inherit at birth, now at the scale of a wounded collective. The only thing more painful than believing some 'great past' has been lost is the revelation that the past was never great at all.

I think about the way the style of Mother 3 deliberately invokes gaming's past, the fact it came out two years after indies like Cave Story and Yume Nikki did the same, that this is two years into the lifecycle of its console's successor, the Nintendo DS. Players at the time would have known that as they were playing Mother 3, its home console was disappearing.

This sense of familial, techno-aesthetic, and historical-collective loss is not just a matter of the game's iconography. Lewis' image of a once-great continent being reduced into islands reverberates through my perception of time as much as space as I play through Mother 3. It's a very fragmented game for its first ten hours, and it becomes gradually more coherent as the player maps its different areas and events. It's a story that begins with lost security, and then puts us on a path of almost gaining something, losing it, backtracking, losing it again, and so on. Put like that it sounds no different to any other JRPG. One could even say that the fetch-quest format, adopted from Arthurian legend and transposed onto fantasy games, is a reification of loss and recovery; a fort/da with sleeping dragons, mole crickets, and arcane shoes. There might be something in that, but too tidy a picture undersells the often frustrating sense of fragmentation that characterises this particular game.

For ten or more hours of Mother 3 we are looking for something, but we don't know what this 'thing' is. The game waits until chapter seven to tell us. The absence of a clear 'thing' across the first six chapters of Mother 3 means we're performing the adventure game ritual aware of the emptiness of desiring metonymy. In lieu of the object of desire we're looking for the thing to look for, if that makes any sense. This instability of time and perspective is what I find most compelling here --- it's like a game looking for a game.

For the first chapter Garland is not 'mother' but 'wife'. We play as her widower, who I've named Rancid. After a night of catastrophe, the people of Tazmily gather around a bonfire. The kids are safe. Property has been destroyed by a great fire. Garland has been killed. Rancid is only worried about that last point. He lashes out and ends up in jail, missing Garland's funeral the next day. He gets out and all the townspeople say things to him like "your life isn't just yours, your kids depend on you" and "at the very least, please be a strong father in front of your children, okay?" In the absence of 'mother', Rancid must become 'father'. He has already failed: while he's in jail one of his sons has gone to avenge Garland, and the other has stayed weeping at her grave alone. Rancid goes after the avenging son. It's a bit like John Ford's The Searchers (1956), and not just because he's dressed like John Wayne. It's the way the solitude of the seeker-revenger is offset by the collectivity of those who remain.

The game is funny, and it wants you to know it's funny, and everything it does must be received through its humour. In the beginning a lot of it is very bad 'meta' gags, where characters comment on the tutorialisation of dialogue and the silliness of JRPG rituals. Garland's death is announced to Rancid via a good news/bad news gag: the good news is I found a big weapon, the band news is I found it lodged in your dead wife's heart. This bothered me at the time but it bothers me less the further I get through the game. I'm not sure whether this is because it mounts a convincing argument that pathos and silliness should coexist, or whether this kind of tonal whiplash is designed to keep me at an affective distance from the tragedy.

What I mean by that is I'm not moved by the death of Garland, but I also know she's not mine to mourn. Instead I feel uncomfortable being in the middle of all the town's grief. I don't know her, and I don't know them. Even as I start to process these things through the central family's pain, the silliness of the outside world continues to interrupt it. There might be something here about our desire for private mourning butting up against the invariably social context of death. In any case I still feel uncomfortable days after the funeral because in the wake of Garland's death the game seems to struggle with what it needs to be. Of course this is deliberate --- it wants to be uncomfortable, and it wants us to really feel the discomfort. The fact Garland's death persists also returns us to the strangeness of the pre- and post-Garland timekeeping of the diegesis. The death of the mother is our introduction to Mother 3, and not something that divides it. There is no time before this originary loss or separation. There is no point in the past where Garnet can be found alive and well, just as there is no actual past to Tazmily Village or the people that live in it.

In the analogy to the loss of the home continent and its substitute in disconnected islands, I mentioned that in playing Mother 3 you gradually map the world as a coherent landmass as you work through it. This is kind of true, although it comes to expand quickly in the latter half of the game. Before this we come and go and return to the same places, getting to know them, and watching as they're transformed with the progression of the game's narrative. (This, along with the pig enemies, reminds me of Tomba! (1997), one of my all-time favourite games). The recursive movement through the Nowhere Islands builds a sense of belonging for the player, while the accelerating flow of time alienates the inhabitants from their home. The more we know of it, the less substantial it's proven to be for everyone else.

My favourite example of this Janus-faced undoing of belonging takes place in the Osohe Castle. The castle seems so ominous and far away in the first two chapters, with the main gate closed, the night setting, and the prevalence of hostile ghosts. By chapter three though it's as local as a friend's house on the same street. With this familiarity comes the emptying of its sense of mystery: the ghosts, once threatening to our characters' in-game wellbeing, appear to have domesticated themselves. The castle is suddenly empty, the bright remainder of something once draped in shadow. This reminds me of Jun'ichiro Tanizaki's In Praise of Shadows (1933), where the author talks about the effects of modernity on domestic lighting practices. According to Tanizaki the shadow is always the potential for something to appear, and its elimination in the form of electric lighting erases the presence of this ghostly uncertainty.

The electric lighting, railroads, and factories of modernity are all heralded by the introduction of money. A cruel and overweight Middle Easterner named Fassad arrives in the Nowhere Islands, determined to corrupt the inhabitants with money, modernity, and the compulsion to happiness. Before Fassad the people of the Nowhere Islands didn't know about happiness, which meant they also didn't know unhappiness. Or, rather, they didn't think of happiness as a thing to be achieved, and therefore unhappiness as a problem to be overcome.

A few things are equally true here. The first is that the business with Fassad is clearly deeply racist. I know the intention is to show the soft power of tyranny in the form of capital, and to celebrate those who rebel. But I also couldn't get out of my head the cute and plucky resistance in the nationalist propaganda film Momotaro: Sacred Sailors (1945), which in Eiji Otsuka's words marries fascist design principles in action and machinery with the cute softness of Disney in its character designs. The second thing is Fassad is a 'facade', and not the real villain, and that, third, the Nowhere Islands are not a real place with a real past that can be corrupted by the influence of people from 'out there'. Xenophobia is, while not vanquished entirely, shown to be based on a series of false premises.

It turns out Tazmily Village is gaming's own village from M. Night Shyamalan's The Village (2004): a simulacrum of an imagined past where the inhabitants can live in denial of the things happening outside its borders. Walking us to these borders, and gesturing to a beyond that cannot be incorporated into the text, models what Jean-Luc Nancy writes of the unconscious, that it "is not at all another consciousness or a negative consciousness, but merely the world itself." What is present is selected on the basis of what "it is necessary for the subject to come to be able to sustain or to bear." Tazmily Village, Leder explains, was designed by those believing "They would start their lives again, in the kind of place they wished they had grown up in." That which is outside the Nowhere Islands is the world itself, but it's also an unsignifiable nothingness.

This twist also mirrors that in the anime Megazone 23 (1985), where it's revealed that the world ended some time ago, and the city we see is a simulation kept alive by the supercomputer Bahamut. When our protagonist asks why the late twentieth century served as the model for the simulation, he's told that it was the period in which the people living were most convinced things were so good they could not get any better. In his seminal Otaku: Japan's Database Animals (2001), Hiroki Azuma describes this as the archetypal expression of Japanese postmodernism. With the cessation of the future the present is suspended, and whether the world ended fifty or five hundred years ago is immaterial.

This late-game revelation critically comments on the conservative restoration fantasy that Mother 3 otherwise appeared to follow. There is no 'thing' to return to. There's also the fact that those who set out to construct Tazmily Village are referred to as 'the people of the White Ship', clearly a reference to the Black Ships which represented the arrival of the 'outside world', and the awakening of Japan from its isolationist slumber twice over. The White Ship reverses the history of the Black Ships, allowing the return to sleep.

For the most part Mother 3 determines we move from event to event, with little chance to wander or get lost in between. It's interesting, the way the suspended time of the Nowhere Islands is cut through by such linear telling. Our every step to progress the narrative brings us closer to breaking the spell of the White Ship's dreaming, destroying the world, and revealing the finitude of the gameworld. This linearity can make it feel as though the game is restlessly pulling us toward this end, almost like a confession.

I'm most interested in what this means for the game as a text. The fact there is in fact nothing beyond the Nowhere Islands echoes the revelation in Link's Awakening (1993), that there is "nothing beyond the sea." That's nothing beyond the skybox, beyond the horizon, beyond the dreaming of the gameworld. Leder tells us the people of the White Ship regret not having come up with a deeper history, to better sell their fiction as a thing with an authentic past. This of course reflexively addresses the construction of the videogame, and the need for it to, at some stage, end. I think the way that games like this bring us to their horizon is important, because it indicates the void around which textual meaning rises and falls. The play of textual finitude, narratively, stylistically, and in the limits and needs of storytelling in Mother 3 is very beautiful.

The self-reflexive humour of Mother 3 serves to remind us that we, and the game, are always performing a JRPG. There are two different, but connected, senses of performance that I'm talking about here. The first is that Mother 3 has us perform a JRPG using whatever tools are immediately available to us, almost like a backyard version of a Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest. If there are no goblins and dragons around to fight, there are paintings, Big Bros, Li'l Big Bros, Bro Teams, and grated yams. If there are no spells to debuff enemies, there are scary masks, tickle sticks, and loud insects that will accomplish the same through more humble means. The second sense of performance is in the way the game's first half feels like a retelling of known events. We jump to different characters' perspectives across chapters, in an attempt to domesticate events that exceed any individual historic actor. The most severe jump is in chapter three, where we play as seemingly minor characters glimpsed in the background of chapter two. It's almost like we're tasked with inventing a past we're otherwise unsure of, having almost got to the start of a reliably linear story of good triumphing over evil.

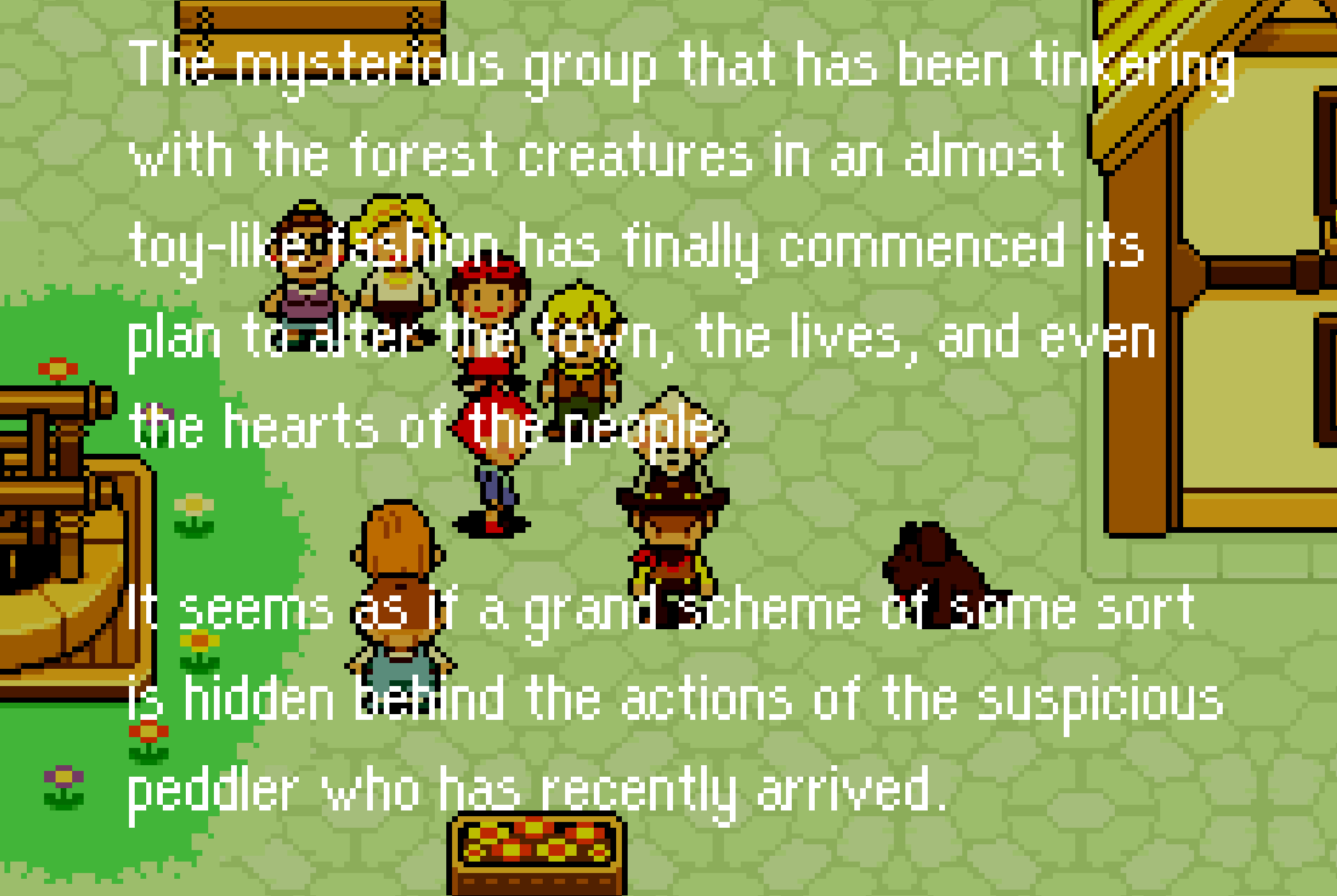

The strangeness of the details, and the unwieldiness of how it all plays out, are all collected by walls of scrolling text that arrive at the end of each chapter, retroactively framing things as an old chronicle. But then this isn't so straightforward --- the experience of discourse time, or the time of play, produces something that exceeds and threatens the integrity of the story. I don't mean that it ever actually tries to overturn it. It adds to that backyard reenactment quality, of a town or community play, with asides and audience interaction, and where everything anarchic about it just shows off how the people involved choose to keep the story alive. This folk quality diminishes as Mother 3 becomes more of a JRPG, focussing on a single group of actors who are granted visibility of, and power over, narrative-historical cause and effect. This may be appropriate, as the transformation of the game's fragmented small stories into a centralised large story coincides with the distraction and then evacuation of the Tazmily Village residents. That is to say, the way history is told is contingent on those who store, tell, and remember it, and the folk-history of Tazmily Village disappears with the disappearance of the Tazmily Village people.

What I like within that is that the group that remain are the group that move events, and that these people in particular were for a while taken out of the time of the game. The main protagonist in particular spends the first three chapters inconsolable at his mother's grave. In chapter seven people comment on how much he's grown, and it's clear that he's only here now because he was the one who took the time to mourn.

Hot springs are the main source of healing in Mother 3. This is very important to me because I'm obsessed with geothermal areas, dams, and waterslides, and am content when a game has even one of these three things. Of the three, geothermal springs are the most important. Every summer before Christmas my mum would drive me and my sister up to see family at the farm they worked on just out of Whangarei. We'd come back for Christmas, then my dad would drive us out to Awakeri Hot Springs, a motel and holiday park just out of Whakatane. The appeal to Awakeri was not the grounds or accommodation, which were gross, but the pools filled with geothermal water from nearby bores. We'd swim in the pools every day until it was dark, and I'd long to return there every year.

In chapter seven of Mother 3, we arrive on an island, eat mushrooms, and hallucinate our way to a Magypsy that helps us sober up. In our sober state we return to one of the hot springs we'd visited earlier, only to find that it's a tip. Not only is it a tip, but it was always a tip. I took this less as a thing about hallucinations and mistaken objects, and more about the pain of returning to a place that once offered solace.

I thought about returning to Awakeri recently but decided against it because returning to things creates an opening where memory is confronted by the real. A colleague from Whakatane recently told me it had gone downhill in recent years, but confessed we might both be remembering it wrong. Maintaining swimming facilities with such hot, mineral-dense water is a demanding task for anyone, and I imagine it's even more difficult for regional establishments like Awakeri. Like many others in Tamaki Makaurau, I am still shaken by the dilapidation and closure of the very popular Waiwera Hot Pools in 2018. My dad often drove us out to Waiwera through the years, and we'd stay 'til the sun was setting and we'd climb the huge rickety wooden towers to the waterslides one last time and look out to the hills and to the coast and see everything glow a final agonising peach before the cold set in with the dark and it was time to go. Still to this day when I'm particularly happy and relaxed I will feel the kind of cold wind that accompanies a sunset, and will smell phantom chlorine.

I wanted to make a quick video about geothermal pools and Mother 3. Having not been to Awakeri or Waiwera since I was a child, the only footage I had on my phone of a geothermal area was from Tokaanu, at the southern end of Taupo. I stayed there in January 2023 on the way back from Castlepoint in the Wairarapa. Much like Awakeri, there are parts of Tokaanu where the geothermal springs have been routed to public swimming pools, and other parts where the springs are left open, billowing steam from fields and bushes.

I made a comic once that features the pools at Awakeri, alongside the dams that were also dotted around the Bay of Plenty. My wife and I are planning an essay film on the subject, but things keep coming up. One of my favourite photographers, Natalie Robertson, did a series on some of these pools, and I'm desperate for her to go back to the subject of Ruaumoko.

None of the frogs in Mother 3 say Give my regrets to the next frog you meet, but at least half of the frogs I encountered seemed to. I'm not sure whether my misreading of their stock phrase (Give my regards to the next frog you meet) started after the death of Garnet or before. If it was before, this would make sense, as I need to book in again with my optometrist, it's been years. If it was after, then this misreading would've been performed in line with the game's investigation into happiness.

If chapter one exists to just reel following the death of Garnet, and two to dash the player's expectation there will be a stable protagonist or narrative object to claim, then three delves into the underlying masochism of the experience thus far. We play as Salsa (I named him ), a monkey accompanying Fassad in his sinister plot to instill a doctrine of happiness in Tazmily Village. Fassad electrocutes Salsa whether he disobeys his captor or not, in a slapstick-style animation that compounds its sense of pointless cruelty. Early on he announces that Salsa can receive an infinity of punishment, and that "You could run to the ends of the desert and I would find you." Fassad's sinister threat repeats a conversation that takes place in chapter two, where Duster's father Wess (I named Duster 'Ches', because he looks like Chesney from Coronation Street) announces that his son can receive infinite abuse, and is so stupid that he'll just keep going. This reminded me quite a bit of Ben Nicoll's talk at DiGRAA this year, where he says games like this expose us to our inability to meet the demands of the Other, and the surplus enjoyment that arises through this failure.

On the surface this relationship does seem masochistic in Mother 3. In the key scene of chapter three, Fassad tasks us with running packages of 'happy boxes' to different people within an arbitrarily decided time limit. The actions required to do this are no more or less enjoyable than any other actions in Mother 3, except that they can't 'feel good' because they're done in the service of a project we probably don't agree with, can't understand, and which we know will fail to meet the demands of Fassad, who will electrocute us however well we perform. Another way to understand this is that Fassad's demands are actually very clear. He wants our sacrifice, our deferral of joy, and playing as Salsa is painful precisely because we do meet these demands. The clear objectives he sets out give us quick access to satisfaction, which is the opposite of the indefinite, fragmented, and frequently alienating path to meaningful enjoyment set out by Mother 3-proper. The TV-like design of the happy boxes is deliberately deployed to have us reflect on what it means to 'seek happiness' as we play through the game.

Is it enjoyable? I don't know --- does it need to be? Does it matter? Here's one of the in-game maps:

As the game comes to an end, each of the Magypsies happily dies in their own way. Ionia becomes like a sheet in the wind. A similar scene appears in B.R. Yeager's Negative Space (2020), but I think it's one of the characters' dads, who is dead, but appears in the room like that. Reading Yeager, we recognise that people are not supposed to appear at the end of your bed, folded like a sheet. What's disturbing about Ionia's death is that the two-dimensional sprite is revealed in its two-dimensionality, but then folds and moves in a way that nothing else in the game has or ever will.

The rigidity of the hearse, and the eerie fluttering of Ionia's death linger in my head. So too does the game's rush to telic emptiness in its final two chapters. Mother 3 is about the end of the world, which in the gameworld is the end of the game; the end that's already there and waiting. It's said Alban Berg's music is an attempt to show sound as it moves to its inevitable disappearance. I wonder about the games that share Berg's geniality with death, and which seem to bring us to the point they can no longer produce any new sounds or images. At that point the game reveals itself to have always been something like a hearse, containing all the lives and stories we made-believe were animate, and that now ask that we lay them to rest. Mother 3 gives us everything it can as a game, just to deliver us to the bare whiteness of the screen.

28 March 2025