Reading too long on Songs: Ohia's The Lioness (2000) one will soon encounter images of despair, desolation, purported evidence that for sole member Jason Molina the world was always already lost. That kind of fatalism attracts listeners because it's safe: there's comfort in melancholia because it casts out the world and mourns something already forgotten. It flatters the ego by destroying it, proud in its having done so before anything else could. I find this characterisation odd, because The Lioness is so clearly fixated on the theme of desire, rather than anything like death. Melancholia would be too easy: melancholia says I cannot be moved. In The Lioness, the thing is always being moved, often in spite of itself. Each song sounds as though it's carefully reworking the last, and so while our position in it remains still, we're left with the world trembling through us. Its characters are always looking, and something's always approaching.

I don't know if it's possible to miss something you never had, but this is how I came to miss Ohia. We were driving to Whatuwhiwhi in the far north, and it had become dusk, and we could smell the dampening hills coming in through the windows. And looking for the turnoff to the Karikari Peninsula we found signs for a place called Lake Ohia. I joked that Songs: Ohia might have been named for the lake, and put on The Magnolia Electric Co. (2003) for the remaining fifteen minutes of the journey. It was the long weekend and we spent the whole time in Whatuwhiwhi, swimming in the cold water and crashing through the bushes of unnamed hills. We must have passed through Lake Ohia and not realised, and thinking back on it I wondered if it was already too dark to see the lake. This thinking back was done much later, a year or more. It was the drive but in reverse: I'd forgotten about the missing lake until I came across The Magnolia Electric Co. by chance in my dad's record collection. I began to miss Lake Ohia near Whatuwhiwhi, because I had missed it without realising that I had missed it. I soon discovered that I had missed Lake Ohia because Lake Ohia is missing.

The most vivid images of Lake Ohia are of its flax industry, taken some time in the early twentieth-century. Google Maps' 'layers' view of Lake Ohia indicates a few disparate patches of blue, while the 'satellite' view shows gridded farmland bisected by an eerie black shape spanning the peninsula. The eerie black shape is filled with symbols for 'swamp' and 'shingle' on the Department of Conservation's topographic map. Lake Ohia is missing because it's a kauri swamp. There was once a great kauri forest, where the trees had grown for thousands of years, and then forty-thousand years ago there was an unknown event that flattened the forest and drowned the trees, and that drowned forest became Lake Ohia. The trees went missing back then, and the lake went missing after that. A 1992 report written by the botanist Brian Molloy describes coming to Lake Ohia to look for the orchids that had grown there, and to advise on whether or not its water-levels should be returned. He speculates on the shores of Lake Ohia and the effects of the lake drainings (first by gumdiggers, second by the Northland council in the seventies), but he makes a plea not to raise the water level of the lake, as the draining appears to have resulted into an influx of orchids. The orchids of Lake Ohia grow atop the forest that was drowned and fossilised and has since been drained. The trees came back dead when the lake disappeared, and the orchids are what grew on them.

When I got home I looked it up and found the musical project was named for the 'Ōhi'a lehua, an Hawaiian tree that grows on lava. One might expect the story of the tree that grows on lava to be about resilience but it's not:

In Hawaiian mythology, 'Ōhi'a and Lehua were young lovers. The volcano goddess Pele fell in love with the handsome 'Ōhi'a, but he turned down her advances. In a fit of jealousy, Pele transformed 'Ōhi'a into a tree. Lehua was devastated. Out of pity, other gods turned her into a flower on the 'ōhi'a tree. Or, some say Pele felt remorseful but was unable to reverse the change, so she turned Lehua into a flower herself. When a lehua flower is picked, rain will come representing the separated lovers' tears. (https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/hisc/files/2018/10/Rapid-Ohia-Death-Poster.pdf)

There are three parties in the story of the 'Ōhi'a lehua. The two lovers and the forsaken. Poet and classicist Anne Carson argues that all desire follows this structure, "for, where eros is lack, its activation calls for three structural components---lover, beloved and that which comes between them" (16). For Pele, Lehua is the obstacle. For 'Ōhi'a and Lehua, it's Pele. In a surprising twist, Pele's revenge unifies the two: 'Ōhi'a turns into a tree, and before long Lehua is turned into a flower. A happy ending. The obstacle that kept them apart now binds them eternal. They complete one another: taxonomists warn against differentiating the flower from the wood. Still, they are defined by the jealous fire of Pele. The fire-red of the 'ōhi'a lehua makes sure of that, and the plant still grows on lava.

And I wanted that heat so bad

I could taste the fire on your breath

Carson describes the three-part structure as a "circuit" of relations that remain "possible" (16). The points on the circuit are "electrified by desire so that they touch not touching;" "Conjoined they are held apart" (16). It would appear that, rather than selflessly uniting the lovers, Pele had extinguished their desire. She alone emerges victorious in her longing. The only conditions that can reanimate 'Ōhi'a and Lehua is the reintroduction of distance: to take the flower in your hand is to make them cry. Pele is mobilised by longing the moment she possesses 'Ōhi'a. Already being one with Lehua, 'Ōhi'a is mobilised by longing the moment he loses her.

And I wanted in your storm so bad

I could taste the lightning on your breath

The ancient forest of Lake Ohia witnessed the Laschamp event. Forty-two thousand years ago the earth's magnetic poles reversed, flooding it with cosmic rays. Researchers were able to consult with the trees embalmed in Ngāwhā, to gather information on how this event affected terrestrial life. The date coincided with the Australian megafauna and Neanderthal extinctions, and with the proliferation of figurative cave painting. The people were in the rocks, and the trees were underground, safe. I wonder what the skies outside looked like, with solar winds lashing the broken magnetic field.

The 'Ōhi'a lehua bears a strong resemblance to the pōhutukawa, a tree endemic to Aotearoa beloved for its fiery bloom. Ecologist Robert Vennall relays the story that Tāwhaki ascended the heavens to avenge the death of his father, but that he fell to his death and the blood he spilled became the red blossoms of the tree. In the version attributed to Henare Potae, Tāwhaki is associated with lightning, and his grandmother Whaitiri, thunder. Tāwhaki and his brother Karihi set out twice to find their grandmother, and on the second journey Karihi fell and died. Tāwhaki descended to mourn his brother, and then took his eyes and gave them to Whaitiri so that she could see. Te Māra Reo, the Language Garden, relays a variation where Tāwhaki falls, and as he's falling plucks out his eyes, and casts them down, and these eyes become the red flowers of the rātā, another in the genus metrosideros alongside 'Ōhi'a lehua, named "te kanohi o Tāwhaki" or "the eyes of Tāwhaki."

I watched you hold the son in your arms while he bled to death

He grew so pale next to you

I first heard the lyric as "hold the sun in your arms." The image of a pale sun must have pushed past the more obvious lamentation of Christ. Either the sun came first because my ears are more used to hearing reference to 'the sun' than to 'a' son in the definite article, or the son came first but was quickly deposed by the pale sun, it being so viscerally frightening. The pale sun/son reflects a pale world:

The world is so pale next to you

The black sun is the central figure in Julia Kristeva's 1987 study of melancholia. She takes it from Gerard de Nerval's El Desdichado (1854), a poem about the prince of Aquitaine, who has found himself "disconsolate," his "lone star ... dead," his lute bearing "the Black Sun of Melancholia." It's not clear who Nerval addresses his poem to, and it's not clear who the 'you' of Coxcomb Red is either, but they both occupy the place of compassion. The temporal relationship of the 'you' to the dead or dying is different, however: Molina's 'you' held the dying as he bled to death, while Nerval's visits him in his grave, where he is already dead:

In the night of the grave, you who brought me solace,

Nerval's narrator is himself dead and entombed. The privacy of the 'you' who visited the narrator in the tomb brings to mind Pascal's Thoughts:

Jesus Christ was dead, but seen on the Cross. He was dead, and hidden in the Sepulchre

Why was he hidden in the Sepulchre? Because "It is there, not on the Cross, that Jesus Christ takes a new life." And why was he able to take on a new life, hidden in the Sepulchre?

Jesus Christ had nowhere to rest on earth but in the Sepulchre.

His enemies only ceased to persecute Him at the Sepulchre.

Nerval's 'you' appears to be one of the saints allowed into the Sepulchre. She may also have been the queen. But which one?

My brow is still red from the kiss of the queen

Nerval's narrator is dead, is visited by the queen in the sepulchre, is brought back to life, is, in this new life, disinherited of the sun's warmth, and left plucking out songs of undeath. The red on his brow remains the trace of a nothingness he'd survived and to which he'd like to return, but can't. The red is the reminder of a wasted compassion, the warmth of the world being lost the moment the prince was able to possess it. For Kristeva this is the disinheritance we all share: emerging from oblivion, and sure to return to it, we endure on the side of life, waiting to be reunited with the thing we cannot name or describe. The red is the mark of life, awaiting lost paradise.

Molina describes the Pietà from afar, as a public scene. The son dies without the promise of new life, and so the son remains dead. But the warmth of the world is not lost for Molina as it is for Nerval. It's located in the 'you' who sits cradling the pale world Nerval's prince is doomed to inhabit, undead. The red shifts place too, from the dispossessed narrator to the 'you' of the addressee:

Your hair is coxcomb red, your eyes are viper black

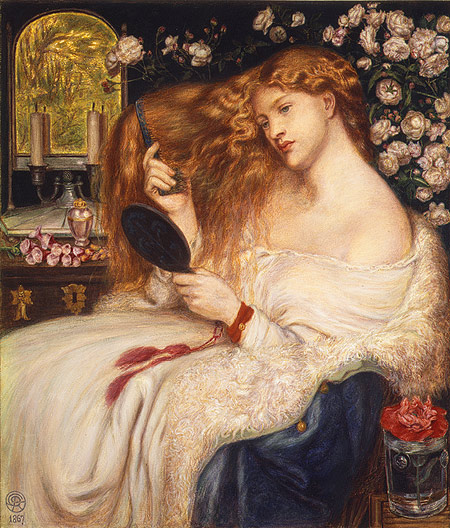

Why is the Madonna given viper-black eyes? For the same reason she's given coxcomb red hair: she's not the Madonna. She's now Lilith, first wife of Adam. Lilith is associated with serpents, owls, demons and the death of stars, infanticide and stillbirth, vampirism, temptation, uncontrolled desire. The appearance of Lilith in the image of the virgin aligns with what Meg Zamula identifies as The Lioness' central theme of predatory women in her contemporaneous review. Howard Schwartz (1975) argues that much of the Lilith folklore emerged from rabbis trying to make sense of the simultaneity in the passage "Male and Female He created them" (Gen. 1:27). For Lilith to be have been present in the interval before Eve she must have been Adam's first wife, and for Adam to have taken another wife each must have been the other's negative: "Lilith is assertive, seductive, and ultimately destructive; Eve is passive, faithful, and supportive" (6). In the 11th Century The Alphabet of Ben Sira it's said that Lilith and Adam fought because Lilith insisted they were made equal, and that when he refused to see this she flew off to a cave and gave birth to many demons. The angels Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangeloff tried to bring Lilith back, and said that if she refused they would kill one hundred of her children every day and she agreed to this.

The son described as bleeding to death in Lilith's arms is one of her own, and one of a hundred children mourned that day. We can assume that, had Lilith returned to Adam, her hair would not be red, and she would not possess the warmth that moves the song.

Why does Molina sing about coxcomb when the flower of the 'ōhi'a lehua is already so red? The coxcomb's generic name celosia is derived from the Ancient Greek keleos, which means 'burning'. Pele's jealous rage cannot so easily be vanquished. It's only the crested variety of the celosia that receives the name coxcomb, because then it looks like the comb of a rooster. Coxcomb meant 'fop' in the Regency era, and it's safe to assume Molina's using it here to denote vanity. Rossetti's famous 1866-1868 painting of Lilith shows her gazing into a mirror, combing her hair. So possessed is she by the act of looking that we can gaze at her freely, and yet her hair reaches out, threatening to strangle us. It must be that, as she looks in the mirror, her gaze is refracted, and sent to us. Why does Rossetti use the mirror, instead of just having Lilith directly face us? Because he wants Lilith to catch us in the act of looking. There's also more to it than that. The folkstory Lilith's Cave tells of a mirror, taken from a haunted house, and given to a young woman. Mirrors are the home of Lilith, the narrator warns, and portals to her cave. As the young woman posed before the mirror, day after day, adoring her reflection, Lilith was watching her through it. Then "one day she slipped out of the mirror and took possession of the girl, entering through her eyes." Now in possession of the girl, Lilith's objective became "stirring her desire at will":

And in this he was right, for the daughter of Lilith that possessed the girl never let her come close enough to any one young man to feel love for him. For if this had happened, the power of the demoness over the girl would have been broken. Instead, she drove her on, commanding her roving eye to seek out yet another.

Far from denoting narcissistic self-satisfaction, the mirror precipitates the girl's becoming restless in herself. Why does Lilith entering the girl's eyes through the mirror stir in her a mad, destructive desire? Because Lilith is desire. But why the mirror? Because on seeing her own reflection she realises that she lacks something she does not, in herself, possess.

Lacan in 1936-49 places the mirror stage in the first six to eighteen months of a child's development, in which they come to recognise in their reflection a coherent being, differentiated from the surrounding world. By the 1950s, however, he no longer sees it as a transitional moment in life, but as a permanent fixture of subjectivity. The image of coherence one sees in the mirror does not coincide with one's ontological lack, Lacan insists, and so the mirror stage works as a site of ongoing misrecognition in the self. Where the image seems fixed and stable, the self is, by its very nature, unstable, lacking. And then when one gazes into the mirror and sees a lacking body, whatever the body may actually look like, this is because the lack in the subject ensures one can only ever detect a lack in the image. The lack that alienates us from ourselves is what generates desire; desire emerges from the subject's pursuit of the thing it believes would satisfy it and make it whole. Because the subject can never be made whole, it restlessly pursues objects that it no longer desires once it has them. This is why desire demands a "roving eye."

You said every road is a good road

Between the next road and your last road

Every love is your best love

And every love is your last love

And every kiss is a goodbye

We can easily see how the desire of the girl in the story is both a) testament to her becoming a human subject, and b) an issue for her social standing. Social suicide needn't be a prerequisite for being true to one's desire, but if it comes to it make sure to choose social suicide.

The mirror image discloses the subject's lack and awakens desire, or eros. Anne Carson brings the three together, "The Greek word eros denotes 'want,' 'lack,' 'desire for that which is missing" (10). The Lioness, as I've said, is about the apprehension before the total decimation of self that is desire. The answer is always to go with desire and decimate the self, because the self is always lacking. Let's compare the painful lack in self of Molina's protagonist to Nerval's prince once more, to stamp out the notion that a destructive love is a melancholic one. The destruction of self for the love of the other is the habit of eros, whereas abdication from the world outside of the self (for the purpose of maintaining its imaginary coherence) is the realm of melancholia. Melancholia's correspondence with narcissism makes sense when one considers their mutual aim: to preserve the self.

In Ovid's myth, Narcissus does not discover the constitutive lack in his being when he gazes upon his reflection. Instead he identifies with its coherence, imagining then that he is a being of great autonomy and self-mastery. Underneath it of course is the lack and disunity of his subjectivity. The image of unity he identifies with is comforting, because it staves off every threat to the self from the world it would otherwise need to sustain itself. This of course is self-destructive, but it's self-destructive on its own terms, without recourse to the world outside the ego. Narcissus is made free from desire and subsequently imprisoned by despair. Nerval's prince is free from desire and imprisoned by despair too. Desire's absence is his disinheritance; it's what makes him suicidal yet unable to die. Kristeva writes that every human subject feels as though it's missing the Thing: the unfathomably precious, unnameable object, that would grant us the unity we're convinced we had at some stage and have lost. Melancholia marks a particular aberration of one's relationship to the Thing. The melancholic knows that no object will deliver them to the Thing, and so they opt to reject desire on the basis that it will never bring them the narcissistic wholeness they feel they deserve. This makes them perilously close to death:

Depressed persons do not defend themselves against death but against the anguish prompted by the erotic object. Depressive persons cannot endure Eros, they prefer to be with the Thing up to the limit of negative narcissism leading them to Thanatos. They are defended against Eros by sorrow but without defense against Thanatos because they are wholeheartedly tied to the Thing. Messengers of Thanatos, melancholy people are witness/accomplices of the signifier's flimsiness, the living being's precariousness

-Kristeva, 15.

The protagonist of The Lioness may want to be defended against the anguish of eros, but it can't be. It's devoted, against its own self-interest, to the self's destruction. And so Molina uses the motif of Lilith, not as the predator of men and children, but as desire, as a force of destruction possessing those unlucky enough to meet the glance of another. It's what drives us to need one another, and its anguish forestalls despair.

And I watched us talking in the mirror

Lilith as red, as destruction, as lack and desire, possesses all. It's what warms the world and makes all else appear pale. It's no wonder The Lioness both craves and fears it: it threatens to destroy what was once known, and to make one other to oneself. We've all encountered the cliche "you complete me," but the experience of desire tends to be one of anguish. In Distillations (2018), the late Mari Ruti argues that the people and things we truly love do not even remotely "complete" us, but rather surprise and confound us, revealing and even intensifying the lack in our being (163). We cannot possess the person we love because they are themselves a subject of lack: incomplete and contradictory (175). To love is to love another, as broken and incomplete as we are. In love we misread and perplex one another indefinitely.

It's for this reason there's nothing solemn about the song Being in Love, which sets up the question in the title and then answers it immediately:

Being in love means you are completely broken

This brokenness isn't an effect of unrequited love, but the condition of coalition. The heart in the song is a gnarled composite of pieces taken from everything it ever loved. In order for it to endure there must remain a surplus, "the one piece that was yours," which is always already forfeited to the other. You only know of the one piece that was yours when you feel it "beating in your lover's breast," because you only sense in the other a trace of the thing you always knew you were missing. And

She says the same thing about hers

Anne Carson writes "When I desire you a part of me is gone: my want of you partakes of me" (30-31). We become aware of the self "at the edge of desire" (39), where it threatens to dissolve into the other. The Greek lyric poets equate changes to the self with its loss, and so "Their metaphors for the experience are metaphors of war, disease and bodily dissolution" (39).

The severity of this fear is part of what produces such moving love poems. It certainly works for The Lioness.

Want to feel my heart break if it must break in your jaws

The printed lyrics to Being in Love run the opening as a single line, as if it were a sentence: "being in love means you are completely broken." But when these words are delivered in song, it's spaced: "being in / love," or "being in...............love," or

being in

love

It's not immediately clear what's being sung when the only words are "being in." The late arrival of "love" is needed to make sense of where we've come from. One could argue the line comes to us broken, and it takes until the second to reveal the perpetrator: the love that breaks the line also breaks the coherence of the narrator. But in another sense it's all a matter of suspense, and it's as though the word needs to be cast out, and anticipated from afar. In one the damage is already inflicted on the narrator, and in the other it's about to happen. I favour the reading of trepidation over ruins.

Why trepidation? Because the work of The Lioness isn't conducted from the ashes, and if it is conducted from the ashes, it's already looking across to the next would-be ruin. I've said The Lioness puts us in a resolutely still position, but that's not to mean it's inert or defeated. Quite the opposite: it's filled with the act of looking across distances.

I will swim to you

"I will swim to you" is The Lioness's moment of rapture, and it's repeated as a kind of mantra so that the moment lasts the duration of the song. Why is "I will swim to you" so moving? Because we don't actually move. The narrator will swim to you. He's not swimming. Swimming remains strictly possible, in the conditional mood: I will swim to you, if you don't get here fast enough. In order to maintain the charge that moves us, his swimming, and her "getting here" would have to meet some kind of obstacle. Carson reminds us "Mere space has power" (18) and that "A space must be maintained or desire ends" (26). The space between them would have to be somehow reinstated. Space moves us because we look across it, and because it is a manifestation of the lack that powers the desiring circuit. We don't move: we will swim. Our position is still because our work is in looking: "For in this dance the people do not move. Desire moves. Eros is a verb" (17).

The look is tangible, I once told a friend who complained that a film was composed entirely of looking. I should have added that the look betrays an eternity that action cannot fathom.

It is for me the eventual truth

Of that look

That wouldn't have persuaded him, and he probably would've disliked the film even more if I'd said it.

There's a sameness to The Lioness that's really symmetry in disguise. Each song seems to quote from every other, and the conclusion to the album reveals the work of a single composition. The playing in the final song Just A Spark makes a point of returning to the chord spacing that opens the album in The Black Crow. The difference is where the opener plays as a dirge toward the inevitable, the strings struck to emphasise the rattling of the low three in conjunction, the closer isolates single notes to obscure the totality of the barre chord. Molina deploys harmonics to fill the laboured spacing with sounds like sparks, and the deliberate use of fret buzz is elevated to the same ghostly register, only now indefinite. It's in the last thirty seconds that a note played starkly outside the implied body of the chord is suspended like a lump in the throat. The only reasonable thing to do after is to play the album again, because the circular movement tells us the lump in the throat was already there.

Just A Spark is both a paring back and a culmination; the point of dissolution and a call to return. The spacing returns us to the opener, while the phrasing is incongruous. Nowhere else do you get the time to dwell on the quality or placement of a single note. A live video recorded a few months after The Lioness was released shows Molina forfeiting the incongruity of the studio version and returning to a familiar strum pattern. The deluxe edition of the album includes a version of the hymn What Wondrous Love Is This, formed through trepidatious picking, harmonics, and a sudden cessation that fills the room, not with possibility, but with emptiness. It must be the basis for Just A Spark, except that it has a sense of finality where Spark points to a return, it has a haunting clarity where The Lioness is searching, and it knows to whom it's singing ("To God and to the Lamb") where the addressee of The Lioness remains a spectral and roaming "you" that cohabits the same sphere of desire and destruction as the addresser. It appears that The Lioness started with and subsequently moved away from clarity as it came together. Maybe as it was shown to other people. It was decided the lyrics needed to be broken and divided across lines, the melodies searched for by the yearning voice and not already known, and the playing simplified so as to give full force to the aberrant note on arrival.

To better appreciate the effects of its simplicity: a number of the songs on Ghost Tropic, released shortly after The Lioness, operate as large, open spaces for the exploration of this technique. Needles of sound arise from the pitch black, hissing against fret and finger. Because melody is suspended in these later songs, the notes take on a percussive function, piercing the dark where the wooden instruments block out pockets of duration within it. Just A Spark is still about disemboweling the recognisable chord as the purported foundation of harmony, and leaking its edges.

You might have thought the story of the orchids growing on the embalmed trees of an ancient forest called Lake Ohia would be a story of resilience, but it isn't. The orchids grow only when the lake is missing.

ohia

1. (verb) (-tia) to long for, desire, dream of, hanker after, set one's heart on, wish for, yearn for, pine.

-Te Aka Māori Dictionary

It was only when writing on distance that I considered The Lioness' cover image was taken from the banks of the Nile, and not the sands of whatever beach appears on the 'Escape to Paradise' sign at the end of Carlito's Way (1993). Carlito is dying. Gail holds him as he grows pale. He receives his Pietà. Then he's carried away on a stretcher by the anonymous arms of paramedics, Gail recedes into the distance, ready to go her own way, and that's where he becomes transfixed by the sign. De Palma forfeits the default tragedy of the Pietà to see if greater tragedy can be mined from a kitsch advertisement. It works. Somehow.

There's a collection of thoughts in Senses of Cinema that might help to explain why. Philip Brophy calls Pacino "the living corpse of exhaustion" and one of the "few actors who you can smell on the screen." We could say the corporeal excess of Pacino dwarfs the classical mortality of the Pietà, and then either manages to grant the sunset image legitimacy, or to so thoroughly abolish distinctions within sentimental legitimacy that all comes to seem legitimately tragic, even or particularly the excessively kitsch. Fiona A. Villella might attribute it to the way De Palma crafts "a plot based on the principle of ephemerality, of transience, of allowing a dream to exist only to have it withdrawn." It's the ad's very ephemerality that makes it mean something, for in this context an image of permanence could only ring as hollow, case in point, the Pietà. Life means nothing, our dreams as much as a tacky ad on the wall of Grand Central. It's an admission that the work's sentiment is no more sophisticated than the one finds in a holiday ad or in You Are So Beautiful, and maybe it earns its tragedy by having us witness someone believe this sentiment means more than it does. Is there a similar admission of the kitsch and ephemeral in The Lioness? I suppose there's nothing more kitsch and ephemeral than a collection of love songs, and maybe that's what the cover is saying.

A word on influence, in light of Pacino. It's Neil Young we come to for the living corpse of exhaustion in song, the musician you can smell through the speaker, whose bones you can feel creaking along the neck. What makes Buffalo Springfield funny is that one of the members is so clearly a ghost and that none of them acknowledge it, and what's curious about that ghost is it gradually comes to possess an old and exhausted body called Neil Young. The Lioness exists in that same region: Molina is haunting the songs of a twenty-first century alternative rock group, and is on his way to possessing a body through which to enact the exhaustion of living dead Americana. Like Young he's approaching timelessness through simplicity, and also like Young, confronted with the timeless simplicity of hymns, he quietly withdraws, cutting the ethereal and replacing it with corporeal error, the clarity of an addressee with a question mark. Nobody knows who they're singing to, not really.

I don't know if it's possible to miss something you never had, but that's how I came to miss Ohia. Like anything one loves, it's still a work in progress, because I still miss Ohia, and in fact I miss it much more now than I did before. Songs: Ohia's The Lioness is a collection of love songs that accumulates in a single love song that dissolves and then returns on itself, ephemeral and always returning. It's never clear who the subject of the love songs is, and that works to its advantage, because the subject is always dissolving along with the narrator and with the song. Anne Carson says that the real subject of love poems isn't the beloved person, but the hole in the poet that caused them to write the poem in the first place. Making and working through art follow the same trajectory, from the lack that propels us to the things outside ourselves, back to the hole that will never go away as long as we live. Carson says what we really want is that absence, that failure to become whole, because it's in absence that we feel eros rush through us. It's not lost on me that this is a very lonely record, but it's loneliness of a different kind. The subject of The Lioness is the chill of loneliness that emerges when we look expectant across a distance, however great, and in dismay we see another looking back.

12 September 2025