Late January 2004 I see Walt across the room. I've not seen him in two years, which when you're thirteen is a hundred and sixty personality changes at least. He sneers and turns away, and I pull uneasy at my hair 'til the bits with split ends come out. Walt had been a good friend. He had got me and my friends into skating, then for intermediate he moved to a private school and cut off contact. Now it's late January 2004, the first day of high school, and to his disappointment we are in the same class again. Our school streams students based on their likelihood to succeed, and our stream is only a few from the very bottom. I wonder if his parents are upset they paid private school tuition fees for this outcome.

A month on we are in PE, and someone has shit in the pool. We have aqua-jogged the pool perimeter as warm up, and the shit has been swept up in the current forged in water. It is moving quickly. It is doing laps. It has become the marker for measuring the rotational speed of our aqua-jog. The gym teacher could have recognised this and told us "that's 0.005 RPM - - I want to see 0.075 by next week," but he didn't. All he sees is a shit being carried along in a current. Class is over early. Walt comes over and says Hey that's a really cool Jackass wallpaper on your Nokia 3315 and would you mind sending it to me. I say of course, and I do, and the next day a group of kids in my class is telling me Hey f*ggot go kill yourself and I look over to Walt and he says Yeah f*ggot. Of 2004 I think anorexia and acne and suicide ideation. I try to make sure to also think skating and Jackass, both of which made life worth living.

I had stopped skating in 2001 because I was getting pains in my knees and ankles. I picked it up again in 2004 as an excuse to go out and smoke weed and drink with my friends. We'd burn CDs, talk about feelings, recall our favourite Jackass stunts. And we'd spend hours at a single staircase, trying to noseslide the rail and heelflip the gap. We'd break elbows and bail and graze skin down to the shy white bone and then do it again tomorrow. The value of it must have been in its very meaninglessness, for skating is the pursuit of failure within an already futile activity. I think it's about the joy of being alive. Now being at a boys-only high school that prided itself on a herd identity built around competition and chauvinistic violence, skating had become a sanctuary. And whether we were watching Jackass or skating bootlegs, it was heartening to see some of the camaraderie and vulnerability we had fostered reflected in the broken bones and spilled teeth on screen.

There is an overlap in the masochism of skating and of Jackass, and it transcends each of their degenerate status. It's a masochism that's peculiarly life-giving, and steeped in the salvation found only in the company of losers. This masochistic salvation is not a retreat from the pain of the world, but a way of being with it. Whether shooting one another with bows and arrows or laughing as the board breaks mid-slide, every second in this mode demands collectively experimenting with and reestablishing the relationship between body and world. In doing so it unearths horizons of the strange and improbable within the everyday environment. But the means by which it is unlocked determine its utility: this new, changing world must remain useless lest the eye goes numb and life retreat with it.

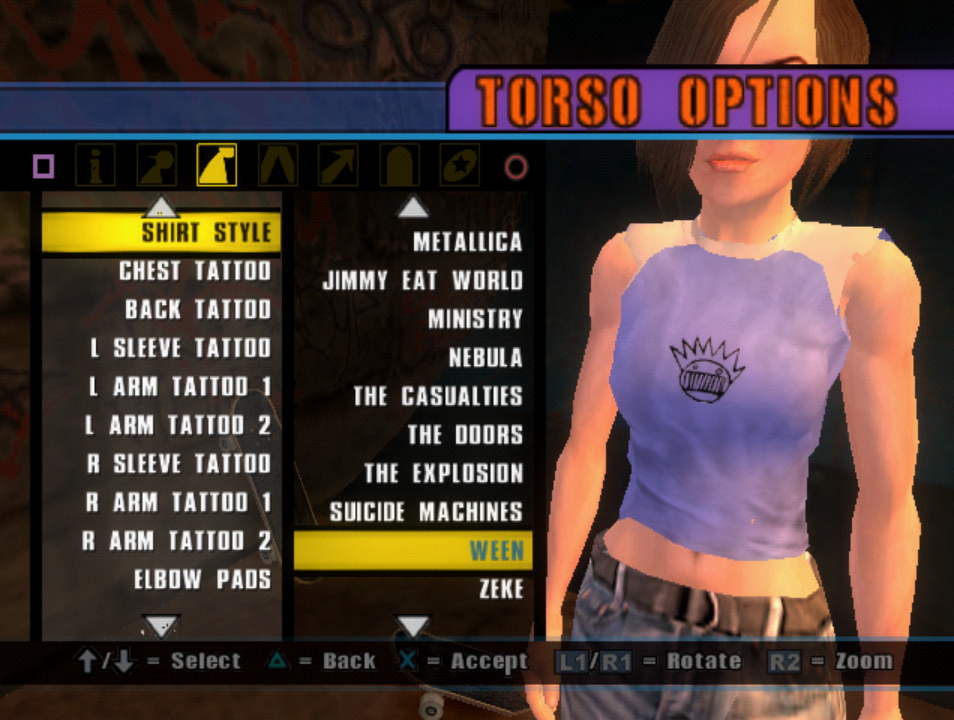

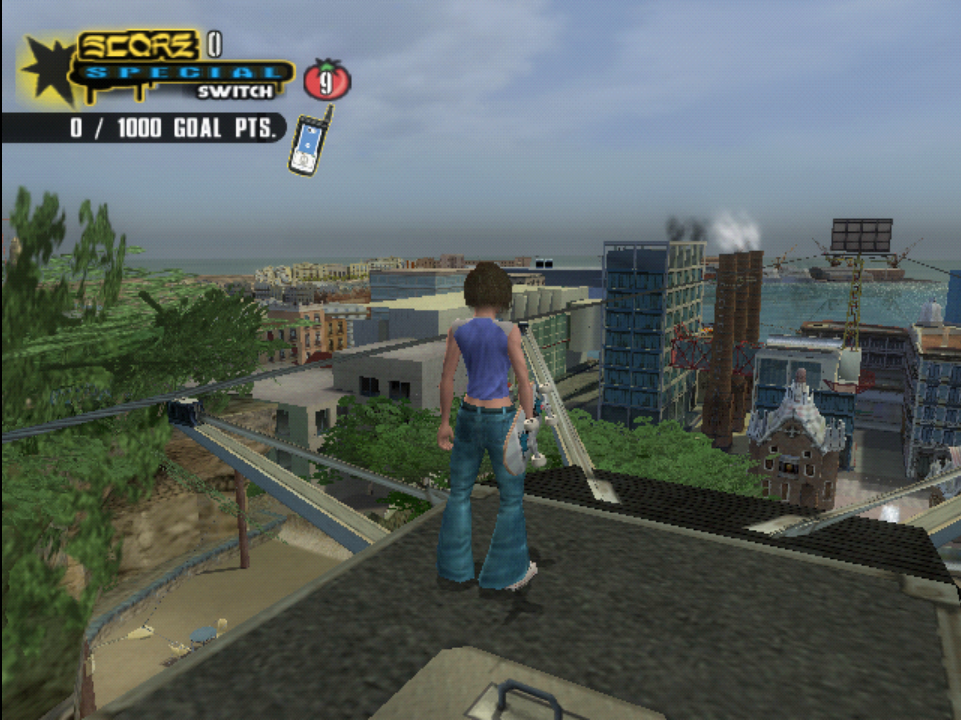

Integral to the Tony Hawk's Underground titles is the idea that you are a nobody. The other Tony Hawk's games are a gallery of real life professionals, but Underground is a database used by nobodies to generate nobodies. Like any character creation database, this one is a time capsule of the prejudices, assumptions, and ambitions of its era.

There are many things to take note of here, but I'll take note of the two most boring things. First: I note there are two different Napster hats. At the time Napster was already vintage - - it had ceased operations years prior. Its inclusion via the hat points to an age of piracy it believes has been terminated. This is for the noble bootleggers of yesteryear, it says. I wonder will skaters in the future wear Soulseek hats, or will there be a crass rehabilitation of LimeWire. I don't know if such a thing is possible. LimeWire was like the KAWS, Carrot Top, or LMFAO of P2P file-sharing clients.

Second: I note that there is a Ween logo under the t-shirt options. This would lead any anthropologist to believe that Ween in 2004 were as popular as Metallica, Jimmy Eat World, and the Doors (?). Continuing their research they will find 2004 was raglan sleeves, Ween logos, and Napster hats. And they'll find it was a time of riding shopping trolleys into walls, getting beat up by Naoko Kumagai, and being willfully eaten alive by alligators.

But to return to the Napster hat. What makes it so evocative is the connection it draws between skateboarding, Jackassing, and piracy. When the future anthropologist tries to figure out how the grassroots masochism of skateboarding and Jackassing came to seize the popcultural imagination at the turn of the millennium, they may well conclude it was the byproduct of end of history malaise. With nowhere to go, and nowhere to be, there was nothing better to do than invest time and injury into meaningless pursuits like kickflips or setting your friends on fire. The anthropologist might also conclude that skateboarding just happened to be the countercultural form that coincided with the widespread availability of consumer-grade videocameras at the time. Jackass hagiographer Nadine Smith writes well on the constellation of piracy that is skate videos, wrestling videos, video art, and Jackass - - the bootleg look and feel of these videos delivers on the quest for 'authenticity' that still occupied the popular mindset after grunge. The anthropologist would then say end of history malaise led to a desire to be punished, or perhaps to explore the limits and capabilities of the human body, either to transcend or to reassert it amidst the ideological and geopolitical abstractions of late capitalism. Probably all of these things were at play to varying degrees, the anthropologist would note, before saying the centrality of the body made this ideal for video, now available to all.

The Napster hat then commemorates the golden age of bootlegs, terminated by the corporate entities that would seize upon skateboarding and greenlight a game like Tony Hawk's Underground 2. Bootlegging sustained the artform now absorbed by the entities that killed it. The future anthropologist will be able to say all of this because they are at such a remove from the time of these things that their appeal is strictly hypothetical, for a hypothetical people. The plexiglass of this empty history will stop them from having to feel any way about the poetry and barbarism of these clattering and ugly artefacts. They will be missing out.

For Tony Hawk's Underground 2's opening tutorial we are told to go back to the warehouse level from Tony Hawk's Pro Skater (1999). There's something very moving about this homecoming. This time we are here as nobodies, and as nobodies we skate around and talk to the professional skaters we played as when we were last here half a decade ago. It underscores our nobody-status, but at the same time puts us in proximity to superheroes.

One of the first tricks we learn is called the Caveman. To Caveman in Tony Hawk's Underground 2 is to stand on the flat ground, holding your skateboard with your hands, and then to jump, placing your skateboard beneath you for the landing. A rich technical vocabulary runs through skateboarding, as with any field that involves the precise description and differentiation of repeatable actions. With this in mind I'm sure the Caveman has its own etymology, perhaps related to how the physical movement appears, but in the context of the game it seems to denote anachronism. It's a way of propelling yourself into the air without the aid of the skateboard. Propelling yourself into the air with the aid of the skateboard is a relatively recent discovery. It came in the form of the flatground ollie. The presence of the Caveman, as an anachronistic technique, is worth discussing, not least because it draws attention to the flatground ollie as an historical, revolutionary force within skateboarding.

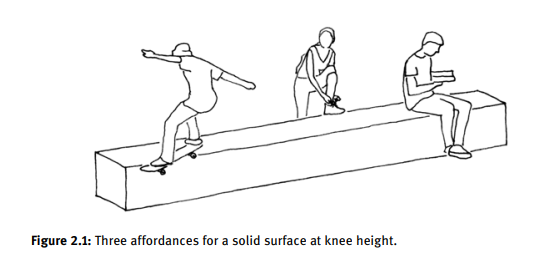

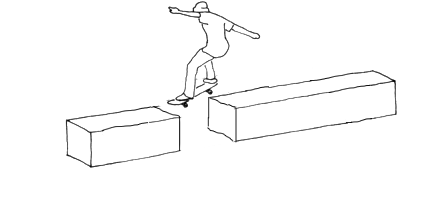

One of my favourite pictures in an academic text is this one in Gregory Whistance Smith's Expressive Space (2022).

I've edited it without permission in what follows to demonstrate how space changes as one's approach to skateboarding changes.

The flatground ollie is so foundational within skating that its presence tends to be taken for granted. It becomes sort of invisible, as it is now difficult to imagine skateboarding without it. But skateboarding is young enough that its histories are stored and told. One of these histories tells that in 1982 Rodey Mullen invents the flatground ollie. He does this by watching Alan Gelfand propel himself into the air using ramps, and wondering whether similar elevation could be achieved on the flat. Mullen's physics-oriented brain solves the problem very quickly. It discovers that if you pop the kick of the skateboard with one foot, drag the other foot upward and along, and then balance the second foot toward the nose, you will indeed find air from a flat, stationary position. It is a complex see-sawing motion that exploits the forces of, and seems to momentarily upend, gravity.

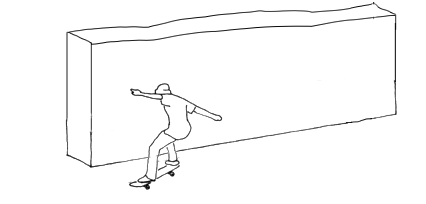

Below is a knee-high surface as it appears to the skateboarder pre-ollie:

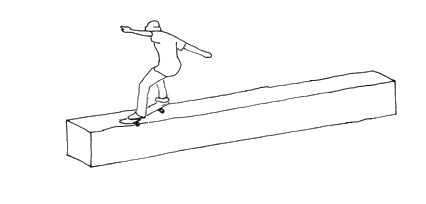

And here is how it appears following Mullen's demonstration of the flatground ollie:

When asked about the flatground ollie Mullen will acknowledge that he did it, but also claim it's "no big deal". He maintains that skateboarding is an art rather than a sport, and that it is communal, and iterative, rather than individual and fixed. For Mullen techniques emerge from communal practice, are returned to the community, and are then developed communally. By this logic he and his community had only modified Gelfand's existing technique, and this technique was in turn modified and developed, is still being modified and developed, will always be modified and developed, and so on. Whether we put this down to Mullen individually or to skateboarding as a collective and iterative artform, the flatground ollie does not so much enter the existing picture as totally shatter and rebuild it. It means the skater is no longer subject to the tyranny of the ground, with only purpose-built ramps to offer respite. It involves a radical reassessment of space and gravity: the ramp is fixed in place, but the plane of vertical activity opened by the flatground ollie is not.

This history continues that in 1986 Mark Gonzales ollies from a wall down to another platform. What Gonzales' ollie does is produce a 'gap' between two objects that previously bore no relationship to one another. This gap is not an absence, but the connective tissue between two things to be imaginatively or physically traversed. With Gonzales' ollie the entire world becomes a thing of gaps, which is to say, relationships to be creatively uncovered and traversed. Where Mullen's revolution is in revealing thin air to be a plane thick with potential, Gonzales' reveals the thickness of the space between all objects. The poetic, fluid, and very technical style of Mullen's skating is made to collide with everyday objects. In this collision the everyday object becomes a thing of poetry. In this poetry, where everything is made thick, both negative space and obstacles become surfaces for connection and expression.

It's a kind of understatement to call the flatground ollie a Copernican revolution for the world of everyday objects. The young history of skateboarding means that we can imagine locating the person responsible for articulating to the world its vertical axis. For taking every one of us by the shoulder and saying You can look, and move, up and down. There is so much more than ground. And for pointing us to the person responsible for articulating the relationship between things where once we thought them siloed, impossible. An eye for the connective tissue of the world is what Tony Hawk's Underground 2 demands when it has us look for, and document, gaps. And, of course, the game asks that we see future action as a constant iteration of everything that's come before. The Caveman does not go away - - instead it marks a way of being with the skateboard, in space, that must be drawn on and connected to whatever comes next.

Tony Hawk's Underground 2 follows the model established by Tony Hawk's Pro Skater 4 (2002), where there's no time limit outside of time-based challenges. Players are able to skate around and explore things at their own leisure, and talk to characters who offer up challenges. We're now so far removed from the arcade-y first three games that arcade machines have been added into the space as a means of accessing arcade modes. The arcade mode is historicised, this new mode elevated to a frame and made 'real'. Levels now are 'open worlds', complete with wandering NPCs, day-night cycles, and weather conditions. Early morning, fog rolls into Boston.

I recall playing this then, and I recall recalling it now, that the open world feels very open when all we can do is skate in it. It was and perhaps is still understood that Grand Theft Auto 3 (2001) so expanded the field of possible action in videogames that it formalised a model by which the player could be made free. (Mostly they could steal cars and shoot things). The sense of freedom in Tony Hawk's games is clearly different, because the field of possible action is moored to a piece of plywood with wheels on it, and there is a point system to tell us our free action must be rationalised through an arcade-game teleology. Still, as I play Tony Hawk's 1 and 2, a sense of freedom rushes through me whenever I am at air or speed, and crashes disappointed over me whenever I fall. The skateboard becomes the means by which I access freedom. It's a freedom that's never pre-given but is worked for, and lost with the inevitable return of gravity.

Movement-negating gravity obtrudes far more in the Underground games than in the main series. Part of this is because the absence of a time-limit means our every thought isn't directed toward maintaining a perfectly fluid sequence of actions. One might even say that a sequence cannot exist without some reference to time, for the sequence temporalises action, and without it actions are only discrete events. The levels in Tony Hawk's Underground 2 assist in the untethering of time and action. They have been designed to communicate to players that the perfect sequence is no longer the objective. The flow of action is repeatedly interrupted by the busyness of levels, each of which allocate a few skatepark-like areas, but have no clear channel to connect them. The objectives given by the game further this disconnected, frustrated mode of play. In the arcade-like Tony Hawk's titles it is possible to fulfil every objective at the same time as sequencing a perfect combo, and landing it all right at the two minute mark. Here we are made to get off our skateboards, to climb towers, to nail a single, stupid action without incorporating it into the flow of things. Indeed there is no time, or flow, through which actions can be sequenced and understood. In Boston one of our objectives is to skate up and decapitate statues. In the Barcelona level, we are to ride into the shit of a bull now terrorising the city centre.

The new disconnected style of play accompanies the depreciation of objectives into stupid bullshit. These stupid objectives are much harder to pull off than the quick and precise combos of the previous games. This is a difficult game, made all the more difficult for its rejection of athletic fantasy and kinetic flowstate. It seems we spend much more time getting up and trying again than we do in the flow of things. What this means is the pleasure found in the game is in the agonising pursuit of the futile, the meaningless. In this way it's remarkably close to the experience of skating. I have this all in mind as I fall into the knotted centre of Barcelona, breaking my teeth across the La Pedrera. Why the fuck am I here? I could try that run again, but why bother? With no time limit, there are no combos. Or rather, the combos never endure. In the infinite time of the level, there is no record of what has happened. The level provides the means by which action can occur but these means are only redeemable in futile gestures garnering an infinity of useless points. All points generated fall away whenever a new trick is performed or butchered. It doesn't matter which.

The depreciation of the Tony Hawk's format into bullshit means drawing attention to the luxury of things. It might seem strange to speak of depreciation, abjection, and luxury, but bear with me. In a recent essay on fashion and futility, Joanna Walsh writes "If luxury is what is produced in excess of an object's capacity to be used, then anything can be luxury - if you just make it useless." Walsh is invoking Georges Bataille on the luxury of unproductive action, the "luxurious squandering of energy in every form." The skateboarder, as I've said, seeks the excess meaning of the everyday environment. This becomes available when its agreed-upon uses are ignored. It's when the handrail no longer functions as a handrail that it becomes a plane of limitless activity for the skateboarder. And having dissolved the function of the handrail, of the bench, of the staircase, and so on, the formal outline of these ordinary objects dissolve too, revealing that they are all connected by the emergent logic of the gap. Having apprehended the uselessness of all things, all things become infinite.

Jackassing pursues the luxury of ordinary objects in a way that appears even more wasteful, because their ordinary use is not replaced with a new (albeit experimental) standard for use via the skateboard. There is something unnervingly truthful about it, as it locates a common nucleus in skateboarding, Buster Keaton, John Waters, and 1970s body art. The nucleus is negative - - the uselessness of things, including the body - - and from negativity it propels life into the unforeseen. Because it requires no real skills, it marks the wanton pursuit of a luxury indistinguishable from abjection. If Bataille is correct that the luxurious squandering of energy tells us more about a culture than its productive outputs, then we can begin to corroborate some of the claims made by the future anthropologist. In a period synonymous with opulent luxury, this was the luxury available to all. And now gaming is of course luxurious because it rejects the utility of the computer's military roots, and calls for the player to knowingly expend world energy (carbon, mineral, water) as well as their own.

One of the ways in which Tony Hawk's Underground 2 is so interesting is that it tethers the luxury of gaming to the painful luxuries of skateboarding and Jackassing. Our expenditure of energy in the game is not frictionless, but a matter of struggle. It's ugly, and stupid, and difficult. It wants us to feel in our bodies the exhaustion of failing and picking ourselves up again so that we can once again fail, and keep failing, in resistance to the beckoning of inertia.

What does it mean to squander the Tony Hawk's game, as Underground 2 is so determined to do? I'm not sure that making a useful argument would be true to the game's preoccupation with its own depreciation, or to the irritated, exhausted experience of play. By adding Jackass to the game, the thing makes a spectacle of its falling apart. There are much more interesting things to be said -- my insights reside strictly at the level of a wastefulness I once identified with, and as I have said, brings to witness actions performed neither for gain nor equilibrium, but to come affable with a dynamic, autonomous force, known by the way it alters the world before our very eyes. Twenty years later I recognise not only the futile gestures that underpin and make it into the game, but also the futile gesture made by the game in which skating is repeatedly obstructed and avoided.

It's said that the next game in the series, American Wasteland (2003), made the decision to once again be about skating and not stupid chaos. But what Tony Hawk's Underground 2 wants us to know is that it's not so easy to extract skating from the chaotic force that guides its poetry and wastefulness alike. I would also add that in emphasising strenuous, wasteful action at the expense of skating, Tony Hawk's Underground 2 actually has skating obtrude into the picture. Instead of taking skating as a given, it constantly toys with the possibility of it being taken away. To explain what I mean by this I will offer a vague description of an article by Elizabeth Balskus, on potentiality and actuality in Giorgio Agamben.

Some time in the fourth century BC, Aristotle writes "A thing is said to be potential if, when the act of which it is said to be potential is realized, there will be nothing impotential." It's generally understood that Aristotle is claiming there exists a field of infinite possibility in the world at any given time, and that when one potential is realised, all other potentials are erased. Two and a half thousand years later, Giorgio Agamben argues that no, we got it wrong. According to Agamben there is an excess impotentiality within every expression of the actual, and this impotence clings stubbornly to everything that is. In other words, everything that eventuates is haunted by everything that didn't. Five years later Tony Hawk's Underground 2 explores the impotential of the skating game, not by removing it outright, but by interfering with it, and keeping it in the margin between the possible and actual. Skating is never more present than when we're made aware of the potential for it to disappear completely. In one sense the game anticipates the end of skateboarding in the zeitgeist, and in another, announces it as a force that will forever haunt its non-appearance.

Now let's return to skating, Jackassing, and meaningless pain. Agamben writes on "inoperativeness", which is the non-being of something as a positive force. Like many others working at the turn of the millennium, Agamben realises there is no historical, spiritual destiny that humans must realise for themselves. Against the strands of conservative triumphalism and leftist nihilism following this realisation, he writes "there is in effect something that humans are and have to be...It is the simple fact of one's own existence as possibility or potentiality." The political dimension of inoperativeness is that it announces that we have the freedom to reimagine the world outside of the calcified power structures of capital, normative society, and state machinery. In becoming inoperable, Agamben insists, we become attuned to the infinite possibilities of the world around us, whether these things are actualised, or whether they continue to haunt what is, pointing us forever to the question of what could otherwise be. I've already covered how skating radically reimagines the everyday. In this view, Jackassing too becomes a revolutionary mode of action. The prophet Ryan Dunn tells of the impotential of a toy race car, Bam Margera a bowling lane, Johnny Knoxville a revolver, Steve-O paper. Freed from destiny, the world awakened, with Jackass as its gospel. Or perhaps everybody was just very bored.

I didn't play Tony Hawk's Underground 2 until the summer of 2005/6, when my sister and I rented it out from the video store in Mt Eden Village. We were living then in a small unit apartment that lay hidden between Ranfurly Rd and Inverary Ave. Over the fence at the Inverary end lived James, and at the opening of the Ranfurly side was Charles, whose father had painted surrealist nightmares all over the walls of their rotted Gothic estate. We had all been friends once, but no longer had anything in common by fifteen. When I think back to that place I think of the deciduous trees that made the streets very shadowy and damp; New Zealand trees are all evergreen, so this stood out. I thought back to that shadow and damp when I rewatched Jackass in March 2019 when Gabriella was in hospital, and the documentary Class Action Park shortly after. I remembered playing Tony Hawk's Underground 2 in 2005 and thinking it was, back then, very much like that decrepit amusement park, all damp grass and trees and grime, and people smiling injured and drunk beneath an impossibly hot sun.

Now I'm finally replaying it and I'm not sure it's all come together like that. Molly and I had Prince playing on repeat, so we never heard the soundtrack. We had all day, so the suspended time of the levels made sense. We had the smell of rotten leaves outside and the sun came through the windows and baked us both alive. We had, I guess, the sense of Jackass and skateboarding as things that were really happening and not just memories signifying some other time or place or idea. Now it's being emulated on a laptop that whirs and panics and sends out electric shocks. Now I'm anxious to find something in it that might never have been there. I text her:

Do you remember when we rented out tony hawks underground 2 one holidays, and it had the Jackass guys in it?

Maybe

It had Barcelona level

Oh yeah

Do you remember anything about it? I'm writing about the game and that's my last memory of it

Idk I had crushes on everyone

The spin the wheel menu? Did we get to bigfoot? I just Google imaged

Yes we did, we somehow got to the end of it

It's a very hard game lmai

Lmao

I can't get past the third level now

You just need me!

Exactly

30 Jan 2025